By Hitomi Yoshida, Research Associate, Temple University Intergenerational Center

Thanksgiving is a time for gratitude, reunions, and celebrations with family. However, many of us have ambivalent feelings about these family interactions. Our mixed feeling can range from the joy of re-connecting to anxiety around different values and expectations that exist within the family, especially between generations. This ambivalence may be experienced every day in multigenerational families, and statistics indicate that immigrant seniors are more likely to live in multi-generational households. Contrary to the stereotypical picture of a large, tight-knit immigrant family surrounding their elders with relevance and constant caregiving support, the nature of intergenerational relationships within immigrant families is more complex. Older immigrants interviewed in the research conducted by the Temple University Intergenerational Center (the “Center”) shared their sense of isolation within their family and community due to lack of time for meaningful interactions, language and value differences, and the acculturation of younger generations.

A Vietnamese senior from Philadelphia expressed his sense of disconnect.

“In Asian culture…parents take care of children, then children take care of parents when they are old…but in America, …[your adult children are] busy spending time working, their children go to school…so these things separate the family…you have to compete with these things [and] there is no room [for elders] to teach about culture.”

The role loss and the decreasing value of elders’ wisdom in American society are major barriers to the well-being of immigrant seniors. As one Somali community leader in Minneapolis explained, “Elders as advisors….that concept is lost here.”

What Can Be Done: Intergenerational Programs

To increase young people’s understanding of aging issues, bridge generations and restore roles for elders as leaders, Project SHINE, the Center’s immigrant initiative, piloted intergenerational programs by partnering with four ethnic-based community agencies across the country: the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia (CAGP), PA; Boat People SOS (BPSOS)-Delaware Valley, Camden, NJ; Confederation of Somali Communities in Minnesota (CSCM), MN; and El Centro de Accion Social (El Centro), Pasadena, CA.

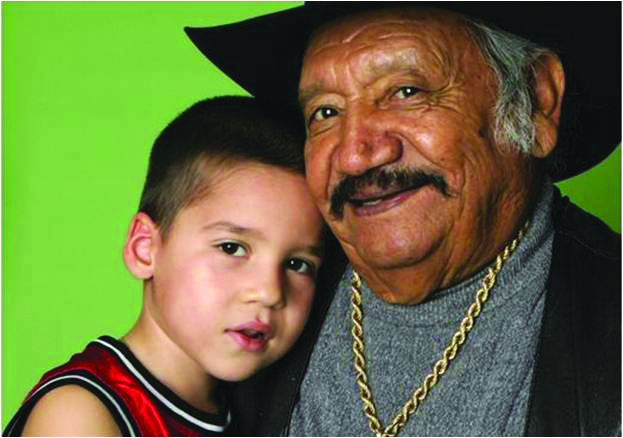

In Pasadena, CA, an increasing number of Mexican-American children are raised by their grandparents. Although they may form an initial bond, as children grow into their teenage years, tension often arises because of the grandparents’ traditional parenting style. Elders lament that their grandchildren are always on their cell phones or computers. Elders in the El Centro’s senior program expressed how difficult it is for them to connect with their grandchildren. Many felt that their teenagers were “spoiled,” “ungrateful,” and “disrespectful.”

Working with the Intergenerational Center, El Centro bridged its senior and youth programs. They guided participants to share their life-stories in a series of joint meetings, and posed questions ranging from “How old are you and where were you born?” to “How did your family migrate here? How did you cross the border?” and “Tell me about the time when you faced a difficulty and how you overcame it?”

Other intergenerational activities under this initiative included a joint advocacy trip to Washington, D.C., a community garden to address food security and preserve cultural heritage, and a local field trip to a cultural site. All sites incorporated story-sharing in their activities to promote active listening between generations. These intergenerational programs emerged as a promising strategy to enhance community-wide support for and leadership development of diverse elders. The key common outcomes for the programs included:

• Building Youths’ Empathy and Support for Elders

The intergenerational activities increased youths’ awareness of the struggles and strengths of the elders in their communities. Participants now believe that aging issues are family and community-wide issues that all generations should engage in. Teenage participants reflected on their experiences:

“You should never judge a book by its cover. I used to think elder people were boring, but they aren’t. They are interesting and their stories are mainly sad….”

“Now I know more about what they (elders) went through and are going through. I know why sometimes they can be angry about the ways things are with their lives…..Why Vietnamese elders are frustrated when they see youth not taking school seriously…some never had educational opportunities like we do.”

• Recognizing Common Struggles

Active listening enabled elders and youths to connect across common challenges they face in their lives. Elders’ perception that “American kids have it easy” has changed through story-sharing. Ms. Pamela Cantero at El Centro reported, “Now they see that young people are going through their own hardships…. they say, ‘Maybe I should just stand back and allow this child to talk to me’.”

El Centro’s Mexican seniors learned that some kids skip school because they experience marginalization at school just like many Mexican seniors do in the community. One senior shared, “I didn’t understand the term ‘bullying’ [before], but after my interaction with one of the students, I was so amazed to hear about some of the stuff students go through.” Another elder stressed the importance of mutual listening. “We must respect their beliefs if we want them to respect ours.”

• Restoring and Developing Elders’ Leadership

Service agencies for the aging often see limited-English speaking elders only as their clients who need assistance. Intergenerational programs have shifted this paradigm by engaging immigrant elders as cultural resources and leaders. Elder immigrant clients can also be contributors and leaders with whom organizations can partner to strengthen families and communities.

Ms. Chanphy Heng, staff at the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia, reflected, “This project gave elders a sense of pride. They think young people are more educated [than they are] and often shy away from sharing their wisdom. Now they feel that young people want to know [about] their life…Even if they do not have a degree or money, they have so much to pass on.”

Possibilities for Deepening Interactions in the Immigrant Families

Elders and youths in the intergenerational projects were not related as family members, yet many participants now see a possibility for developing a deeper relationship with their own grandparents and grandchildren based on their experience in the intergenerational program.

One Vietnamese-American student told me that she never had a sit-down conversation with her grandfather who lives close by. Now she wants to listen to his stories.

“I feel this has become more of a necessity…If I don’t listen to his story, it will be lost ….If I can do this with elderly who are not my family, why can’t I do this with my own grandpa?”

• The Intergenerational Pilot Projects were made possible by the support of MetLife Foundation.

Hitomi Yoshida is a Research Associate at the Temple University Intergenerational Center. She conducts community-based needs assessments and evaluations with immigrant and refugee communities. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.