I am carrying my eight-month old grandson around the house, trying to help him let go and go to sleep. As I chant “Ne-ne Ko-ko, Ne-ne Ko-ko, Ne-ne Ko-ko, Yoh-oh” (sleep baby, sleep baby) over and over, I remember my grandmother carrying me on her back before my afternoon nap, chanting the same thing. I can almost feel myself in both roles at the same time – grandchild, grandparent. A special magnetism helps span these generational roles.

Just Enough Distance

While my relationships with son, daughter and elderly mother are very active and dominated by the present, when I interact with my grandson and my granddaughter I’m often thinking about my past and their future. I am remembering my grandmothers – my grandfathers both died before I was born – and imagining my grandchildren remembering me.

I wonder what they will make of the story about Grandma Suzuki’s purse? I used to lie on Grandma’s bed as she sat in her chair crocheting and sometimes she let me explore the contents of her purse. I loved the way she would unpack and explain its contents – hard candy (always), tissues, rubber bands, a small plastic bag for restaurant leftovers, glasses, I.D., paper and pen. I learned about the Great Depression through her thriftiness, as expressed in her purse.

Grandma Suzuki was my ally. I remember her standing up for me a few times, against my parents’ criticism. In retrospect I think it was because, although she lived with us, she could see my situation from some distance that my parents didn’t have.

The Legacy of Ethnic-Cultural Identity

Seeing my grandchildren allows me to map the flow of my family’s ethnic* and cultural identity.

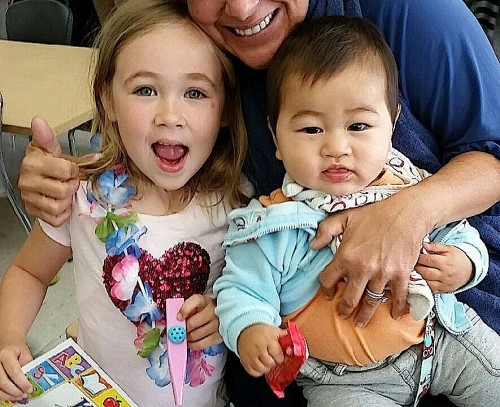

My Hapa** granddaughter has green eyes set not too deeply, a nose like mine, fair skin and strawberry blond hair. To the outside world she’s Caucasian although she’s ¼ Asian. She has a recessive gene for blond hair that snuck into my Japanese-Chinese DNA from a distinctly non-Japanese person. As I think back to that unnamed ancestor I wonder how my granddaughter will form her racial and ethnic identity.

My Hapa grandson has dark brown hair, and brown almond-shaped eyes. To the outside world he’s seen as Asian, although he’s ¼ German. Though still a baby, he seems to have inherited a stocky German build. And I wonder how he will form his racial and ethnic identity.

We are shaped by what others see in us more than I’d like to think. To some extent my grandchildren’s identities will be formed by their appearance and how others interpret their ethnic identity. Still, I hope to contribute what I received growing up with a Japanese-speaking grandmother and parents who spoke only Japanese until they entered Kindergarten. Some through line of leaving rural Japan for the U.S., settling in California and surviving the Great Depression, being uprooted and sent to concentration camps in the desert during World War II, resettling in the Midwest and starting all over and, for me, growing up in an all white community and being called out regularly for being different until I reached California.

My grandchildren both share this strand of family history, and I will be curious to see how they use it to construct their identities.

Family Stories

Perhaps because my parents and grandparents left behind almost nothing written about themselves, I’m particularly interested in passing on family stories that say something about our values and how we’ve lived our their lives as a result.

My maternal grandmother worked in a large sweatshop after she came to Chicago and was living with my mother and father. She took the bus to and from work and sometimes brought piecework home to sew and make extra money. My mom said that they knew Grandma was a really good seamstress. Grandma told me that one winter it was so cold as she waited for her second bus that her fingers were numb and the bus transfer fell out of her hand without her knowing it.

I was aghast when I found out that both my grandmothers had worked in a sweatshop, but my maternal grandmother was quite matter of fact about wanting to work and not stay home all day. All the ladies were Japanese so it was a good environment. To my young girl’s mind she seemed nonplussed by it all but in retrospect I realize that her husband had died about that time, most likely from the stress of losing his business when he was sent to concentration camp and that she had been uprooted from her community in Pasadena, California and lost most of her possessions. It was gaman that I was seeing – “enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.”1 This is a uniquely Japanese and highly prized trait that doesn’t extend much past me as a Sansei (third generation). Though my kids know it and have observed it, I think it will likely be only an interesting cultural trait for my grandchildren.

Experiences that I share with my grandchildren will resonate through their lives in ways I can only imagine.

Reflection

I write all of this in the hope that my grandson and granddaughter will remember and reflect upon their Japanese and Japanese-American ancestors, as remembered and lived through me, and that they will pass some of this along to their grandchildren.

*I use the term ethnic because “race” is a social construct, not a biological phenomenon.

**Hapa – “of part-white ancestry or origin.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

1 The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946, Delphine Hirasuna, Ten Speed Press, Berkeley.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.