by Neil Gonzales

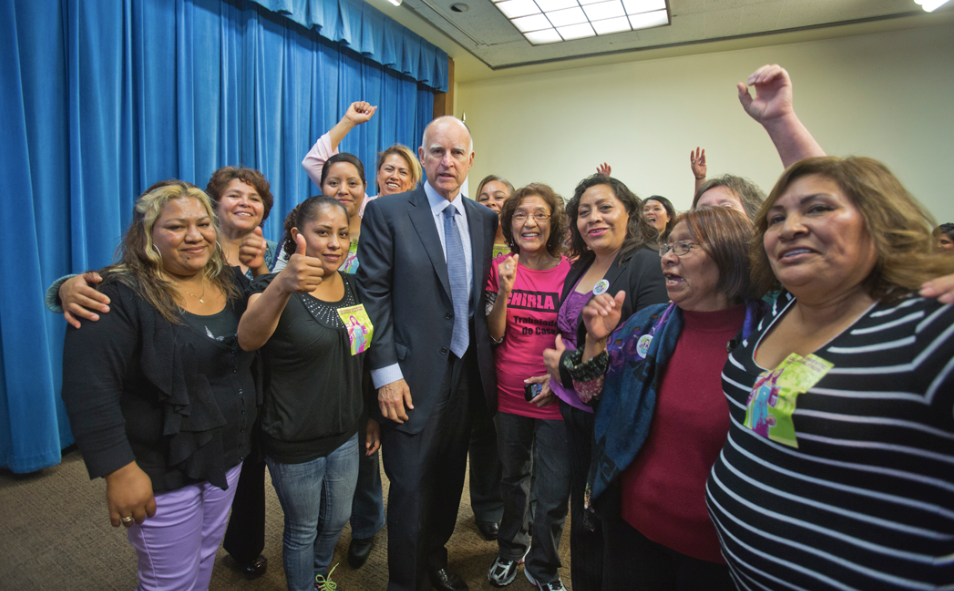

Domestic workers and California Governor Jerry Brown cheered after he signed the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights into law on September 26, 2013.

As a caregiver for nearly 10 years, Lea Nelson enjoyed the interactions she had with her elderly clients.

“The exchange of stories while eating meals, doing their nails, coloring and cutting their hair, and massaging,” she said. “Playing with them board games, mind games and card games.”

But Nelson, who provided one-on-one care at a home for seven years and served in a nursing facility for a year in the San Francisco Bay Area, also often had to stay awake through the night caring for the seniors and experienced other difficult working conditions.

“It was extremely hard,” she said.

Conditions Put Seniors at Risk

Recent studies only underscore the plight that caregivers — many of whom are Filipino such as Nelson — must endure because of their work environment. For them the work often involves sleep deprivation, staffing shortages and inadequate pay. All of this puts their vulnerable clients at risk for poor care, neglect or even abuse.

It was quite a challenge “taking care of elderlies by yourself who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and needed a lot of attention and care,” said Nelson. She is a naturalization counselor for Filipino Advocates for Justice, a community-empowerment group based in Oakland, Calif. She also witnessed mistreatment of both fellow caregivers and their clients.

One study co-authored by Jennifer Nazareno, a postdoctoral research fellow at Brown University’s Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research, explored the work and sleep situations of Filipino live-in home caregivers in Los Angeles.

According to the study, the caregivers averaged 6.4 hours of sleep and rated the quality of their sleep significantly low, negatively affecting their work. Also, more than 40 percent of the caregivers reported excessive daytime sleepiness.

“Live-in caregivers experience frequent sleep interruptions at all hours of the day and night to attend to patients’ need,” the study said. “The resulting impacts on sleep quality pose risks for both work-related injury and errors in patient care.”

The findings stress “the tenuous nature of private residences serving as formal work environments,” said Nazareno. She presented the research during the World Congress of Gerontology and Geriatric in San Francisco in July. “These prolonged periods of [working] in patients’ homes mean (the caregivers) are essentially on-call” and do not enjoy the protections that exist in traditional workplaces.

These kinds of work-related concerns are only likely to persist or even worsen given the demand for caregivers because of the increasing numbers of seniors and other factors. By 2050, the population of Americans age 65 or older is projected to double to nearly 84 million.

Live-in caregiving is “one of the fastest growing jobs in the country because older adults want to age in place and don’t want to be institutionalized,” Nazareno said.

“There’s a large participation of Filipinos in the industry not just in the U.S., but Italy, Japan and Qatar,” she also noted. “They are working in the shadows still. They don’t want to come out and talk about exploitive conditions.”

Study: “Understaffed and Overworked”

A report titled “Understaffed and Overworked,” released last May by the Coalition for a Fair and Equitable Caregiving Industry, a group made up of legal-service providers, community organizations and others, found that residential care facilities for elders (RCFEs) – as opposed to more highly regulated skilled nursing homes – are not required to have licensed staff either on site or on call.

“Many caregivers often work around the clock without proper pay, adequate sleeping facilities or sufficient sleep,” the report said. “Frequently, small RCFEs do not keep records or keep inaccurate or false records of hours worked. Misclassification of workers as independent contractors and retaliation is prevalent.”

Basic wage compliance also remains elusive in RCFEs, which are also called assisted living facilities or care homes, the report said. Since 2011, caregivers in California have filed more than 500 wage-theft claims with the state Labor Commissioner’s Office.

Of the cases that have made it to a hearing, caregivers have won judgements amounting to $2.5 million, the report said. However, $1.8 million have remained unpaid.

“Shortage of staff combined with long hours results in worker fatigue, which increases the risk for errors,” said the report, published by Golden Gate University School of Law. It notes, “Caregivers have not been properly trained and supervised to deal with the acute levels of care needed by residents. Understaffing and poor training compounded by rampant wage violations create high levels of stress for caregivers that impact the quality of care and life for RCFE residents.”

Vincent Pettis, president of the American Caregiver Association, described the coalition’s report as offering “evidence that has been known for quite some time in the caregiver industry but has yet to be adequately addressed on many levels.”

He added, “As the national certifying body for caregivers, our primary role is to provide caregivers with the tools, techniques and strategies they need to perform their job at a high level, providing the highest quality of care they can to our seniors.”

“As our organization looks ahead, we hope to expand our role into areas beyond certification and into closer proximity of the day-to-day real issues facing caregivers, seniors and their families, as outlined in the study,” Pettis added. “We are truly excited about the opportunity to do this and look forward to leading the way on many fronts.”

Domestic Worker Bill of Rights

Other efforts to improve caregivers’ labor standing have been under way. In 2013, California became the third state to pass the Domestic Worker Bill of Rights. The law grants overtime pay to caregivers and those in other household occupations, if they work more than nine hours in a day or 45 hours in a week. A follow-up legislation signed into law a year ago took out a sunset clause, making the overtime protection permanent. New York and Hawaii have enacted similar laws.

Advocacy groups such as the Pilipino Workers Center in Los Angeles have also been pushing for the establishment of contracts that clearly stipulate pay, meal breaks, uninterrupted sleep time and other basic labor standards, Nazareno said. Filipino live-in caregivers “do want to be recognized as workers, and having that employer-employee contract will help do that.”

In spite of some breakthroughs in recent years, “many of the caregivers we have spoken to are not aware of their rights,” said Geraldine Alcid, executive director of Filipino Advocates for Justice, “and many continue to struggle with harsh working conditions such as being on call 24/7 for an insufficient base pay, doing tasks beyond their caregiving duties and being grossly underpaid.”

Neil Gonzales is the Chief Correspondent for Northern California at Philippine News. He wrote this article with the support of a journalism fellowship from the Gerontological Society of America, New America Media and the Silver Century Foundation.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.