by Kayla Sawyer. This article originally appeared on the NICOA blog.

TRIGGER WARNING: If reading this post triggers past traumas, please see the resources listed at the end of this article for assistance.

There is a serious lack of meaningful government data documenting rates of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. A recent study by the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) revealed that only 116 of the 5,712 cases of murdered or missing Native women were logged into the Department of Justice’s nationwide database.

U.S. attorneys’ offices declined to proceed with 37 percent of cases from Indian Country, according to a 2017 report published by the Department of Justice. Seventy percent of those declined cases were due to lack of evidence.

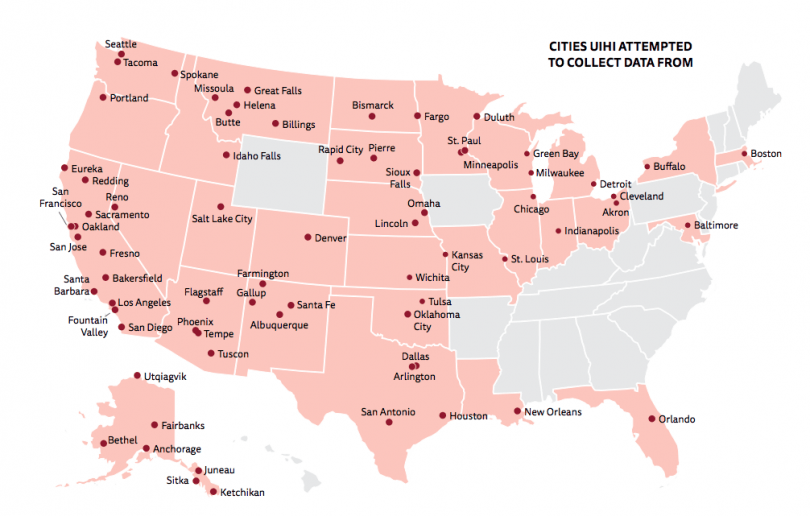

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports that murder is the third leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women and rates of violence on reservations can be up to 10 times higher than the national average. However, no research had been done on rates of violence among American Indian and Alaska Native women living in urban areas, even though 71 percent of them live there. A lack of data and an inaccurate understanding of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls creates a false perception that the issue does not affect off-reservation American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

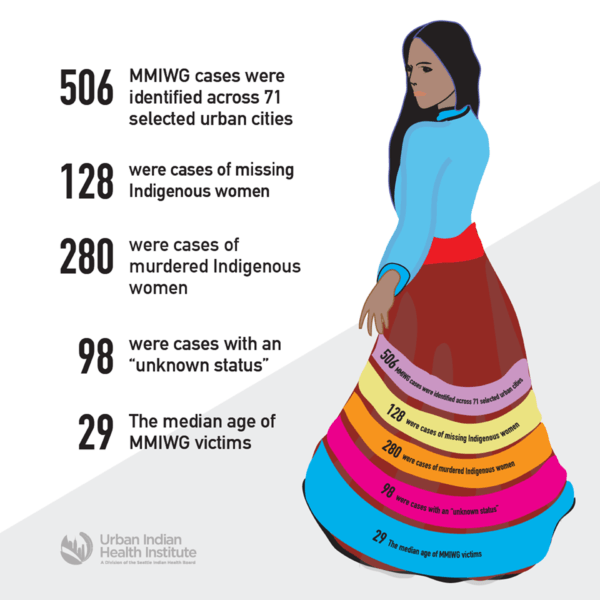

UIHI identified 506 unique cases of missing and murdered American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls across the 71 selected cities — 128 (25 percent) were missing persons cases, 280 (56 percent) were murder cases, and 98 (19 percent) had an unknown status. Approximately 75 percent of the cases UIHI identified had no tribal affiliation listed. Sixty-six out of 506 cases were tied to domestic and sexual violence.

Of the perpetrators UIHI was able to identify, 83 percent were male and approximately half were non-Native. Twenty-eight percent were never found guilty or held accountable. Under federal law, tribes only have sole jurisdiction in crimes in which both perpetrator and victim are Native American, and even then, the most serious crimes — including many domestic violence offenses — are automatically sent to the federal government, which declines to prosecute many tribal cases.

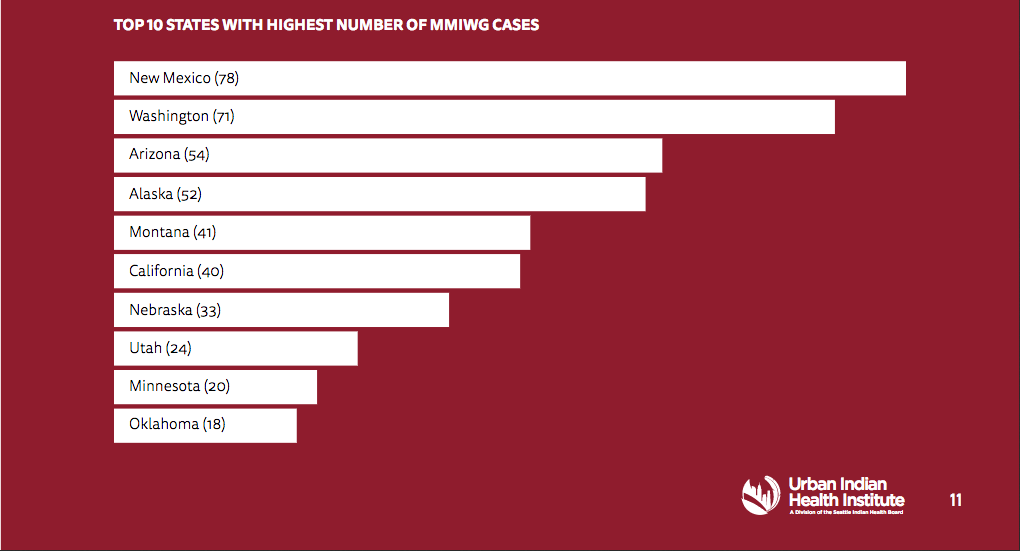

According to the report, the states with the highest number of cases were New Mexico (78), Washington (71), Arizona (54), Alaska (52), Montana (41), California (40), Nebraska (33), Utah (24), Minnesota (20), and Oklahoma (18). The areas with the largest number of urban cases with an unknown status were Albuquerque (18), San Francisco (16), Omaha (10), and Billings (8). Both Albuquerque and Billings police departments acknowledged Freedom of Information Act requests but did not provide any records or information.

When asked how many Native American women have gone missing or been murdered in a given city, nearly 60 percent of police departments either did not respond to the request or returned partial or compromised data — with some cities reporting an inability to identify Native victims, and others relying exclusively on human memory.

The hearing comes shortly after the Senate passed Savanna’s Act. The bill is named in honor of Savanna Marie Greywind, a 22-year-old woman from the Spirit Lake Nation who was brutally murdered after she went missing in North Dakota last year.

If enacted into law, the bill would require the Department of Justice, for the first time, to provide annual reports on the numbers of Native women and girls who go missing and murdered. It would also require the government to improve access to national databases to ensure that such cases aren’t forgotten.