by Grace Birnstengel. This article originally appeared on Next Avenue.

Chances are, there’s at least one person in your life who identifies within the LGBTQ community — likely more than one. The person might be a family member. Or a neighbor. Or a friend’s child or grandchild.

Though messaging about, and support of, LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) people has progressed in recent years, the community still faces hate crimes, employment and housing discrimination, barriers to health care and harmful bias. That’s why allies are so important.

An “ally” is someone who supports LGBTQ people and equality in its many forms — both publicly and privately. Heterosexual and cisgender people can be allies as well as those within the LGBTQ community who support one another’s unique needs and struggles.

The key qualities of an ally are a desire to learn and understand, to help LGBTQ people feel supported and included and to address barriers to fairness and justice for everyone.

Below are five ways to practice allyship. Keep in mind that LGBTQ people are all different, define the practice differently and therefore seek different types of allyship. Don’t assume every LGBTQ person in your life is the same.

1. Unlearn historical messaging

Before you can be an LGBTQ ally, you must identify, unpack and challenge stereotypes and unconscious bias. It starts with knowing a little history.

Homosexuality was criminalized nationwide until 1962 when Illinois became the first state to decriminalize it. Homosexuality was considered a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association until 1973. Messaging around the 1980s AIDS epidemic spread damaging misinformation about the LGBTQ community. The “don’t ask, don’t tell” United States military policy prohibiting gay and lesbian Americans from openly identifying and serving in the military was reinforced in 1996 as well as the Defense of Marriage Act barring the federal government from recognizing same-sex couples in any legal manner.

“Go back and rethink all of the information you were taught before. Stop and reflect and say: ‘Does this reflect the people we know that are LGBT?’” says Bob Linscott, assistant director of The LGBT Aging Project — a nonprofit in Boston. “Even if people have a solid grasp of history to know this was not accurate information at the time and don’t believe it, what most people don’t realize is how that has impacted LGBT older adults.”

2. Educate yourself

To understand a community, you must understand their past. And there is a lot to learn.

The modern-day LGBTQ civil rights reached a turning point 50 years ago, with the 1969 Stonewall riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York City. Though much transpired before Stonewall, it’s a good place to begin learning, and gives context to why LGBTQ pride is celebrated in June. PBS’ Stonewall Uprising special is available to stream online, and you can check your PBS affiliate station for local broadcast times.

Terri Clark works as a trainer and consultant in retirement communities, assisted living facilities and aging services on the topic of LGBTQ allyship in Philadelphia. She recommends allies read books by, or about, LGBTQ people. Many libraries provide reading lists during June for LGBTQ Pride Month or have entire sections related to LGBTQ issues and history. The Chicago Public Library offers their reading list digitally.

Clark also suggests attending trainings or workshops in your area about its LGBTQ community or allyship. Check your local LGBTQ center or PFLAG chapter for upcoming events.

3. Learn and use correct and inclusive language

In the LGBTQ community, language is everything. It’s important to use the right words and pronouns when referring to someone or describing their gender identity or sexual orientation. Never assume someone’s gender identity or sexual orientation. Ask if you’re unsure and if it’s appropriate.

“Don’t presume everyone you’re talking to is straight,” says Serena Worthington, director of national field initiatives for LGBTQ elder advocacy group SAGE. “Just because someone has kids doesn’t mean they are straight.”

Here are some basics:

LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer.

Queer is historically a derogatory word (and still sometimes can be), but has been reclaimed by many in the community for its ability to be an umbrella term. The word means different things to different people, but generally refers to sexual and gender identities other than heterosexual and cisgender.

Bisexual refers to someone who is attracted to people of the same and different gender identities as themselves. People who identify as bisexual don’t need to have had equal experience or equal levels of attraction with people across genders, nor any experience at all. Attraction and self-identification determine orientation.

Cisgender means your gender identity aligns with the one you were assigned at birth.

Transgender means you experience and express gender that does not match the one you were assigned at birth.

Gender non-conforming means a person identifies as neither a man nor a woman. Many gender non-conforming people use “they/them” pronouns. If you’re unsure of someone’s pronouns, just ask. A good way to breach the conversation could be saying: “I use she/her pronouns. What are your pronouns?” Some people prefer the terms genderqueer, genderfluid, genderless or nonbinary. If you’re unsure, again, just respectfully ask how someone identifies.

It’s always best to use gender-inclusive language like “folks” rather than “ladies” or “guys” and to use “spouse” or “partner” rather than “husband” or “wife.” The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Emerson College, and the University of Maryland offer inclusive language guides online.

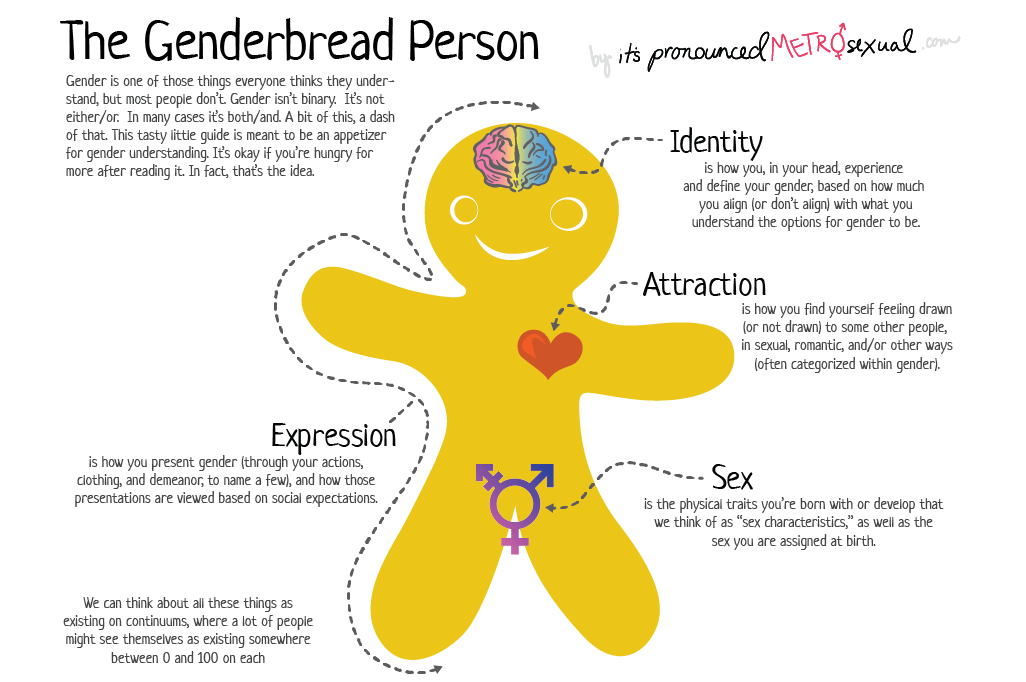

Below is a teaching tool called the “Genderbread Person,” which illustrates the difference between anatomical sex, gender identity, gender expression and sexual orientation/attraction. (Click to enlarge)

The National LGBT Health Education Center, NYU’s LGBTQ Student Center, PFLAG and GLAAD all offer more expansive terminology glossaries to study and practice. The GLAAD guide includes terms to avoid and what to use instead.

4. Listen to those within the community

“Have conversations with diverse LGBT people and learn about their experience and their history,” says Clark. “Be intentional about finding diverse groups to be with.”

To show your support and interest in LGBTQ peoples’ lives, ask good questions:

- When did you know you were [lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender/queer]?

- What was it like growing up?

- How did you know it was the right time to come out?

- What was the coming out process like?

- How can I best support you?

Preface the questions by stating that the person shouldn’t feel pressured to answer or share anything they’re not comfortable sharing, and make sure you’re in an appropriate and safe setting to talk about potentially heavy or triggering memories.

These questions should be saved for people you already have a relationship with — not a casual acquaintance or new coworker. And always maintain confidentially when asked.

Note: No matter how close you might be with a transgender person in your life, do not ask invasive questions about a person’s body or surgeries they may or may not have had.

5. Speak up or intervene

Don’t tolerate anti-LGBTQ jokes or statements expressed in your presence.

“If someone misgenders someone or says something that is not true, correct them rather than making the LGBTQ person correct that themselves,” says Worthington. “That removes the burden from the LGBTQ person.”

For more on allyship, see the Human Rights Campaign’s “Coming Out As a Supporter” resource, PFLAG’s “Guide to Being a Straight Ally” and PFLAG’s “Guide to Being a Trans Ally.”

Grace Birnstengel is a writer and editor for Next Avenue, currently leading an editorial initiative on age-friendly health care — what it means and how people can identify and access care that meets their unique needs. Her other areas of focus include LGBTQ issues, mental health, the arts and ageism. Grace holds a bachelor of arts in journalism and gender, women and sexuality studies from the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities. You can find her Next Avenue work here.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.