Born in Santa Ana, CA, to two Muslim refugee survivors of the Cambodian genocide, Hatefas Yop wasn’t aware of her family’s use of public services when she was a young girl. After all, her peers in her elementary school all hailed from the local neighborhood, where many immigrant and refugee families had to live in one-bedroom apartments subsidized by Section 8 housing. She didn’t understand the melancholy in an elder whom Hatefas referred to as “Grandma,” when she said her food stamps (paper at the time) weren’t ‘real money.’ “But you could use it to buy food,” Hatefas recalls saying to her.

“I was just trying to understand a lot of the sadness and the hurt from people in my community, but I didn’t realize it for myself until I became older that I began to see folks had access to other things that I did not have,” she continues.

In middle school, Hatefas noticed that her life was different from the students from other demographics and income brackets. She realized she had reduced lunch, and that going to the doctor only happened when something was extremely concerning or severe. “Access to healthcare was something completely foreign,” she says. “We didn’t grow up having regular doctor routines.”

****

After crossing the Thai border from Cambodia and living in a refugee camp in the Philippines, Hatefas’ parents, Yop Ris and Maysom Yusuf, arrived to Santa Ana in January 1980 and were expecting their first child. Two of Maysom’s sisters also resettled in the United States; it would take four more years for them to reunite after being scattered in different states. Because Maysom was adept at making sure her family had the resources they needed, Hatefas said she and her three other siblings didn’t worry about food. The Southeast Asian American mothers in her local community together mastered gardening and applied for food assistance with help from local community organizations such as The Cambodian Family Community Center — “Mothers always made sure their children and families always had enough to eat,” says Hatefas.

After crossing the Thai border from Cambodia and living in a refugee camp in the Philippines, Hatefas’ parents, Yop Ris and Maysom Yusuf, arrived to Santa Ana in January 1980 and were expecting their first child. Two of Maysom’s sisters also resettled in the United States; it would take four more years for them to reunite after being scattered in different states. Because Maysom was adept at making sure her family had the resources they needed, Hatefas said she and her three other siblings didn’t worry about food. The Southeast Asian American mothers in her local community together mastered gardening and applied for food assistance with help from local community organizations such as The Cambodian Family Community Center — “Mothers always made sure their children and families always had enough to eat,” says Hatefas.

Meanwhile, Yop Ris’ focus was on how to survive financially. The then-20-something-year-old made donuts at a local donut shop, where he made just $25 a night to supplement the welfare checks he received to support his family, while going to adult school to learn English. He later would sponsor two of his teenage cousins. Hatefas credits Section 8 housing and food assistance programs for making it possible for her father to be able to provide shelter to others. However, despite the deep responsibility Yop Ris felt for his sponsored family, “in some ways, he lives with a guilt that he didn’t provide them with what he needed,” Hatefas shares. “I reassure him that things were out of his control.”

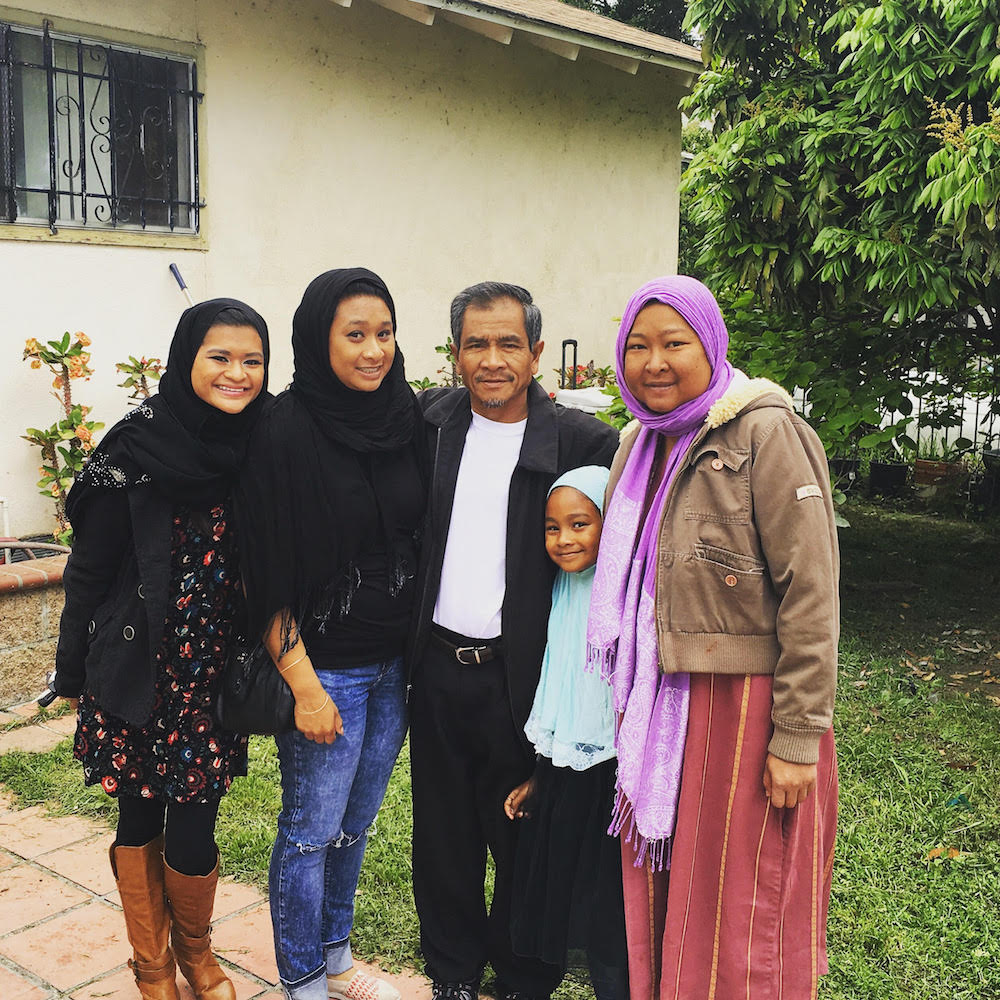

One day, a regular at the donut shop where Yop Ris worked, encouraged him to check out a local community college program that offered welding classes. He enrolled, and ever since and for close to 40 years, Yop Ris has worked as a diesel vehicle mechanic. “My dad was able to find stable employment, and because of his friend in the donut shop, he was able to buy his first home, which he still lives in now,” Hatefas says. “He could have lived anywhere, but he bought a home 20 steps away from his Section 8 housing. We still live in the very same community where our family resettled in.”

****

Today, Hatefas is pursuing her degree in Asian American studies at California State University-Long Beach after having worked as a community organizer and advocate of culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health services at The Cambodian Family Community Center. She hopes to remove the stigma of using public services, a stigma that she is quick to point out is not meant to be applied holistically to her community but rather something she and her family personally felt. And she rejects the silencing and fear that the Trump Administration’s proposed public charge rule inflicts on immigrant and refugee communities.

“Sometimes it’s forgotten that folks within the Southeast Asian American community did depend on public programs in order to establish their families,” she says. “In my perspective, public charge further silences the big economic disparity we face. It further silences the struggle to reunite families—and we have to remember why our families need to be reunited.”

What Hatefas hopes for most of all is empathy. “Community members who are eligible for these programs need the help. By penalizing them for using these services, it puts into their minds that every small encounter can possibly jeopardize their life in America,” she says.

“I have the privilege of being born here, and I will never comprehend my parents’ trauma and weight that they had to carry with them leaving behind their homeland, but to wonder how to find a place to live, or get food for their family, or access proper medical care, or feel like they are not safe, and also not wanted—after going through such a traumatic experience, that’s heavy.”

To learn more about what’s at stake under the proposed public charge rule, check out SEARAC’s toolkit.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.