By Grace Birnstengel. This article originally appeared on Next Avenue.

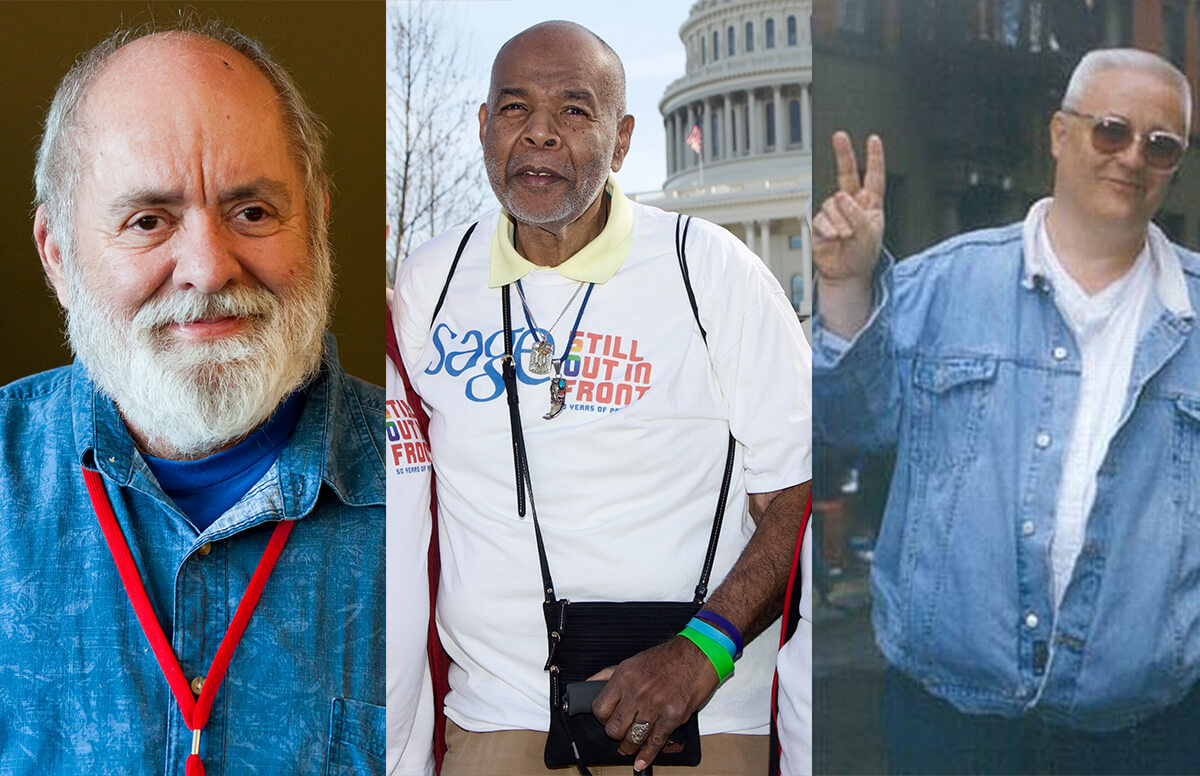

Jude Patton, Roger Macon and Jeremiah Newton — three men who lived through the “Stonewall era” (credit: those who are pictured)

Multiple conflicting accounts exist of what happened June 28, 1969 at 53 Christopher St. in Greenwich Village. And really, the Stonewall Inn rebellion in New York City that day is just one piece of what really sparked the modern LGBTQ movement across the nation. Here are stories of three men who — at Stonewall that night or elsewhere — have deep connections to an era of painful protest, discrimination and liberation:

“Jeremiah, They’re Raiding the Stonewall”

Unlike “everyone in the world,” Greenwich Village-dweller Jeremiah Newton didn’t attend Judy Garland’s funeral on June 28, 1969. He didn’t really know her; he only saw her in passing at the bars. Instead, Newton found himself at Jacob Riis Park, a popular gay beach in Queens, New York. But on June 28, Riis Park wasn’t popular at all. It was empty. Everyone was at the funeral.

So Newton headed back to the Village. The 20-year-old ran in circles with artists Andy Warhol, Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling (who Newton went on to produce and narrate a movie about) and could be frequently found at the Stonewall Inn.

“This guy I knew from the bars named Shelley, he comes running down the block toward me and said ‘Jeremiah, they’re raiding the Stonewall.’ I said ‘That’s not new,’” Newton recalls. Police raids at bars were an accustomed part of gay existence in 1969 — and years after.

“He said, ‘This is different.’”

According to Newton, police officers were told by deputy police inspector Seymour Pine to close down the Stonewall. The police were clearing people out of the bar and carrying out boxes of liquor. Inside, police officers broke toilet bowls, mirrors and, what Newton calls “a beautiful jukebox.”

Newton in Christopher Street Park in 1992

“People didn’t like that. They really didn’t,” said Newton.

As Stonewall patrons exited, they joined a crowd across the street.

There was a police officer guarding the door and, Newton said, “swatting his club against his arm.” Drag queens taunted the officer and eventually someone threw a bottle. It landed over his head and shattered; the officer ran inside the Stonewall.

“Seymour Pine came out and said, ‘Who threw that bottle? Step forward.’ And people just looked at him and started throwing bottles at him. He scurried inside like a rat,” Newton said.

At the 25th anniversary of Stonewall, Newton met officer Pine who, according to Newton, revealed that had someone thrown, say, a cocktail or bottle while officers were inside, the police would have opened fire. “He was ashamed,” Newton said.

Many understand the Stonewall rebellion as one night. But three consecutive nights of turmoil between police officers and bar-goers is bookended by innumerable police raids and years of subsequent raids, marches, protests, rebellions and riots in cities across the country.

“That night was the birth of the largest movement in the world, little did we know,” said Newton. “We just knew it was unusual. We just thought the cops were so f—ng stupid.”

The June 28, 1969 Stonewall rebellion stands out in history for its marker of when we recognize LGBTQ liberation efforts annually.

Newton was at the first annual Gay Lesbian March in 1970 (now the New York City Pride March), which looked a lot different than how we conceptualize a Pride march today. There were, he said, “no floats, just people.”

The New York Times said 10,000 people marched then, but Newton estimates three times as many did.

“Nobody knew what was going to happen. Would someone with a gun shoot at us? Nobody knew anything. It was amazing,” he recalled.

An Arch Enemy

Roger Macon was working his job taking care of thoroughbred horses at the Long Branch Racetrack in Oceanport, N.J. when he saw on television the news that something big was afoot at the Stonewall Inn just 50 or so miles from where he was working.

“They called it a riot — the news did — but it was a rebellion against oppression and equal rights,” Macon, now 71, said.

Macon became an LGBTQ activist, participating in demonstrations, marches and volunteering at hospitals that treated HIV/AIDS patients.

Much of Macon’s activism culminated at the historic St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan.

“Cardinal [Terrence] Cooke was very anti-gay,” Macon said. “St. Patrick’s kept the door shut during the march, and then the Cardinal kept speaking his foul language about us — we’re perverts and all kinds of stuff. Cardinal Cooke was our arch enemy.”

Macon (right) and his partner Marc Cruz

Macon remembers stopping at the Cathedral during the annual Gay Lesbian March in the early-to-mid-70s and “really yelling and protesting.” One year, protestors handcuffed themselves to the railings, resulting in the railings being removed. Fast forward to the early ‘90s, Macon went into the Cathedral after the march and during mass, walked down the aisle with a male friend and embraced him in front of everyone as an act of resistance.

Macon hopes that even with the increased rights of today’s LGBTQ people, the work doesn’t stop.

“We’re all getting older, and we’re not going to be around much longer,” he said. “I hope the younger people keep up the fight because it’s still going to be a battle. The doors have opened a lot, but they can close just as fast if people don’t keep the momentum up.”

Singled Out

Jude Patton wasn’t at Stonewall, but he experienced intolerance and police raids at gay bars in St. Louis in the early 1960s. A transgender man in his early 20s then identifying as a butch lesbian (the closest description he knew that got at how he felt), Patton was singled out and asked to leave gay bars because he was “too much” — too out, too gay, too butch, too masculine. He had a crewcut and wore men’s clothes, which Patton describes as “extreme for those times.”

“The bars thought they could get by with the other people who were there,” Patton said.

That didn’t stop Patton from hanging out at St. Louis gay bars like Shelly’s Circus Bar and Betty’s California Bar. The raids were predictable: often in the fall, during an election year, “because someone would make a promise to get rid of the gay and lesbian bars,” said Patton. There were “off-season” raids, too, but activity really ramped up during political years.

Patton in 1964

After nearly five years in St. Louis (where he had moved from small-town Alton, Ill.), Patton relocated to southern California in 1965 in search of a more open and welcoming community.

“After all the rejection and emotional experiences, I thought if I stayed in St. Louis I would die,” he said.

He had friends in California who said it was safer and more comfortable for LGBTQ people than in the Midwest at the time.

A coworker at the veterinary hospital where Patton groomed dogs gave Patton a copy of Dr. Harry Benjamin’s groundbreaking The Transsexual Phenomenon, which helped Patton finally understand his identity.

“There was the description of me and people like me,” he said.

Patton, now 78, started hormones in 1970 and was Stanford University’s third female-to-male patient to undergo complete sex reassignment surgery. In his lifetime, Patton said, he’s witnessed the Women’s Liberation Movement, the sexual revolution, the drag bar scene and the transgender movement. He continues work as an activist, educator and advocate.

Grace Birnstengel is a writer and editor for Next Avenue, currently leading an editorial initiative on age-friendly health care — what it means and how people can identify and access care that meets their unique needs. Her other areas of focus include LGBTQ issues, mental health, the arts and ageism. Grace holds a bachelor of arts in journalism and gender, women and sexuality studies from the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities. You can find her Next Avenue work here.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.