by Ling-Mei Wong. This article originally appeared in Sampan Newspaper. To read this article in Chinese, click here.

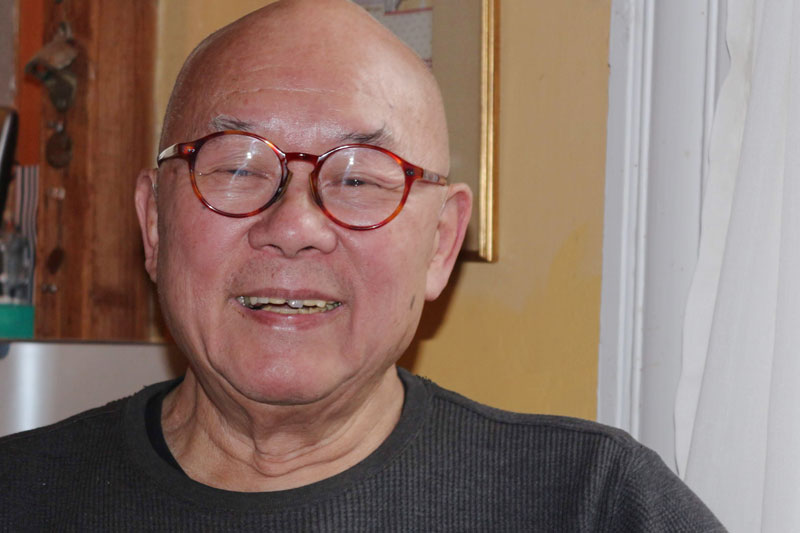

Artist Wen-ti Tsen, 83, is influenced by war and immigration in his work. (Image courtesy of Ling-Mei Wong.)

Between art shows and exhibitions, you would never know Wen-ti Tsen is 83 years old.

“Being an artist means not following a set pattern of retiring at 65; nobody ever stops working,” Tsen said. “The older you get, you think better. You have fewer distractions.”

Tsen’s portfolio includes a Chinatown mural of Chinese garment workers, with a model displayed at 38 Ash Street, the Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center lobby. His “Home Town” project featured 12 figures of everyday Chinese people from the Chinese Historical Society of New England’s archives, which he placed throughout Boston Chinatown in 2016 and at Lexington library exhibition in 2018. Tsen created the “Asian American Comic Book” with the Asian American Resource Workshop. In 2017, he produced a mural at Tufts University with Tufts and Museum School students, working with Asian American Studies professors Lisa Lowe and Jean Wu.

“All my work has involved politics and art,” Tsen said.

Tsen helped mentor Ngoc-Tran Vu, a Vietnamese American multimedia artist and organizer based in Dorchester. Her 2017 work “Community in action: A mural for the Vietnamese people” incorporated community input to tell the journey of Vietnamese individuals to Fields Corner.

“Wen-ti understands communities and what collaboration is all about,” Vu said. “For the projects he’s working on with the Chinese community in Chinatown, he goes back continuously. It’s not a one-off thing. It’s truly mission-driven work to highlight underrepresented stories that are often times forgotten or misrepresented.”

Budding artist

Tsen was born in 1936, to high-ranking official Tsen Tsonming and painter Fang Junbi in China. His father died when he was 3, killed with bullets intended for Chinese President Wang Jingwei.

“I was 10 for the first time I went to school in Shanghai,” Tsen said. “From 1945-1948 I was in school and did terribly. The best thing I did was to skip classes. It influenced the things I do now.”

As Shanghai swelled with refugees from the Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese civil war, Tsen recalled seeing the body of a dead girl on the street. Despite the dire circumstances, Tsen and his elder brothers enjoyed a privileged childhood with tutors, servants and weekly films.

“I would sit by people in streetcars,” Tsen said. “I had no pocket money, so I was intrigued by rental picture books and would read over someone’s shoulder.”

By 1948, Tsen’s mother decided to return to France. She was the first Chinese woman to graduate from the École des Beaux Arts in Paris during the 1920s, marrying her husband in 1922 before moving back to China in the late 1920s.

Tsen joined his brother and mother in the United States, settling in Brookline. “In 1961, I lived on Beacon Hill, where there were still a lot of Chinese laundries and a bachelor society,” he said. “I remember seeing a man ironing away when I went out, then when I’d come home at 11 p.m., I’d still see him working. I could see some food in the back, then piles of laundry.”

To commemorate Chinatown’s working-class roots, Tsen wants to create four life-size bronze statues of a cook, a woman at sewing machine, a grandmother caring for children and a laundry man. He wants the statues at ground level, instead of elevated on pedestals.

“You should feel the connection of looking at someone,” Tsen said. “Little kids can climb over them.”

Living

After Tsen completed his Museum School studies, he traveled for two years by car from Paris to Pakistan, then to Egypt. He then taught art at the Museum School.

“I was involved with the Vietnam War protests. The FBI was investigating me,” Tsen said.

Newly married to his wife Alice, Tsen was offered a position teaching art at an American prep school in Beirut, Lebanon. He enjoyed three “peaceful and lovely” years, before they moved back to Cambridge in 1972 and started a family. Their two daughters live in Chicago and Dayton, with the Tsens purchasing a Chicago condo to visit their grandchildren.

While Tsen has loved his colorful life, writing a memoir is not a priority. “I want to meet interesting people, rather than share my story. I think that will keep a person alive longer,” he said.

He prefers to think of mortality in terms of 2,000 days, prioritizing his time as his strength fades. “Two thousand days sounds different than six years. If someone asks me to do something, such as an art project for kids, I can decide if I want to spend the day drawing on a sidewalk or not. Every day has to be a meaningful day.”

Tsen recently went on a retreat to Texas, reading the “Tao Te Ching” and reflecting on the idea of “do nothing.”

“You’re open to hearing new things and accumulating new knowledge, instead elevating oneself,” he said. “Everything is alive.”

This article was written with support from the Gerontological Society of America, Journalists Network on Generations and The Commonwealth Fund.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.