by Jaya Padmanabhan. This article originally appeared in India Currents.

“What did you eat today?” my mother, Sarada, begins her phone conversation with my twenty-three-year-old daughter in New York. When my daughter explains that she made rasam and sautéed cauliflower over the weekend, Sarada’s face lights up. Later she tells me she’s happy that all her grandchildren love rasam, a staple broth from the south of India.

Eighty-six-year-old Sarada immigrated to America in her 70s, and finds equanimity performing activities and engaging in conversations that hinge around food. When she meets people she doesn’t know, she connects through food conversations, often recalling the piquant tastes of her youth.

Familiar flavors act as a barometer to her moods, often alleviating the stress of adjusting to a brand-new environment and she looks at food as the one constant in her new life, which she uses to bridge the gap between her past and present.

More importantly, when Sarada does not have access to familiar foods, she displays signs of acute emotional distress, appearing physically drained and listless.

Eating—A Social Event

Sarada, waiting for her order at Saravana Bhavan, a south Indian restaurant (photo courtesy of Jaya Padmanabhan)

Sarada entrenches socialization in the act of eating. It is true that in most cultures, meet and greets occur around food: we go to restaurants for dinner, have potluck get-togethers and have affinity gatherings where food is conspicuously on display. Sarada, who re-contoured her physical, geographical and cultural spaces later on in life, finds that she is unable to participate in these social gatherings because unfamiliar food becomes alienating.

What complicates the Indian experience is that the cuisines of the different regions are distinct, right down to the staples and vegetables. Southern Indian cuisine uses rice, tamarind and coconut gravies, which differ from the wheat breads and tomato-onion-ginger flavors of the north.

As she ages, Sarada has become more and more particular in her dietary needs, eschewing food that is not from her home state of Tamil Nadu in India. This has affected her socialization patterns, limiting her and isolating her, even within the Indian American community.

And she’s not the only one who feels this way.

What’s On Your Palate?

With over a decade of experience directing Stanford’s Aging Adult Services program, Dr. Rita Ghatak, a gerontologist and psychologist, is the associate director of Optimal Aging Center, and—along with her husband—is a caregiver for her father-in-law, Gopala Pillalamarri. She observed that her father-in-law’s biggest preoccupation is food, particularly food from India’s southern state of Andhra Pradesh, well-known for its tamarind and chili flavors.

While living in India, Pillalamarri, a former journalist, seldom went to a restaurant, preferring home-cooked meals. And on the rare occasions that he did go to a restaurant, it would often be to a restaurant serving the same dishes he was used to eating at home.

He moved to California to live with Ghatak and her husband in the ’90s, along with his wife. While she was alive, his wife regularly made food that satisfied his palate. At the time he would go on long walks with a cohort of older immigrants and seemed to have adapted to his new country. After his wife’s death, he began to gradually decline, socialized less and less and became increasingly insistent on eating foods that he’d enjoyed for most of his life.

“[Ghatak] makes Bengali food, and I taste it once in a while, but I don’t like it much,” Pillalamarri said, with an apologetic grin.

A typical south Indian meal. (Photo courtesy of Jay Jayaraman)

Other Cultures, Similar Stories: Give me kimchi!

Eighty-seven-year-old Korean American Chang Song Lim lives alone in an apartment close to Boston. Lim came to America in 1989 and his first job was as a factory assembler in Springfield. Within a year, the factory closed down and he was laid off. With his limited English skills, Lim has had to work many odd jobs, including dishwashing and cleaning.

Once he retired, Lim signed up for the government assisted meal service program. He had to choose from American, Russian, Italian and Chinese offerings. Figuring that Asian food was the closest to his Korean palate, Lim opted for Chinese. “It’s a different taste, a different style,” he told me. His body was not used to this type of food, Lim explained, adding that it was causing a serious problem for him. “I’m very skinny right now and I’m indirectly killing myself. I just want kimchi,” he said, the stress clearly audible in his voice.

___________________

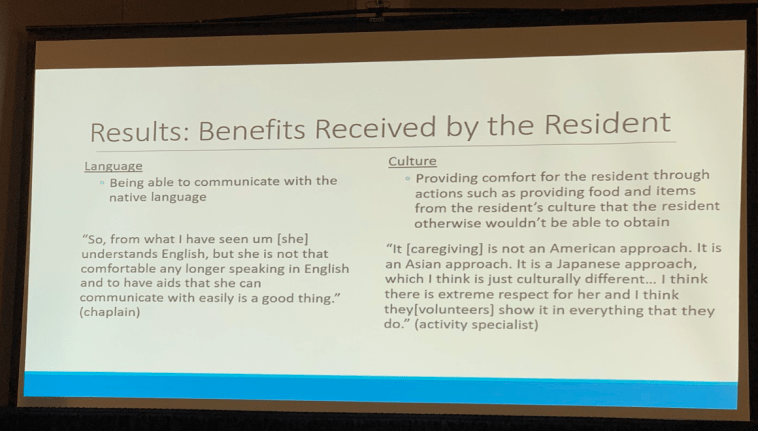

“Older ethnic immigrants face greater challenges in alleviating their loneliness and social challenges because of their language and cultural barriers and small social networks,” said Megumi Inouye, a researcher at George Mason University, at the Gerontological Society of America’s (GSA) annual conference this year.

In a longitudinal study of a senior immigrant Japanese woman who was in long-term care in Boston, Inoue quoted the husband saying that his wife wasn’t eating much and had little appetite. But when a volunteer interacted with the woman, she asked the volunteer to “spend more time and bring Japanese food along.”

A slide from Megumi Inouye’s presentation at the GSA 2019 Scientific Meeting. (Photo courtesy of Jaya Padmanabhan)

A Rising Trend

With the steady pipeline of older immigrants arriving and aging in the United States—in 2010, more than one in eight adults, 65 years and older, were foreign-born, according to the Population Reference Bureau—it’s critical to have conversations on what drives the emotional health of immigrant seniors, since emotional health affects physical health, and both these have economic costs associated with them.

And even among the foreign born, the older Asian population is growing definitively. Dr. Vyjeyanthi S. Periyakoil wrote in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (May 2019) that the older Asian American population is “projected to quadruple from 2 million in 2014 to 8.5 million in 2060. This ethnogeriatric imperative underscores the great and growing need for healthcare services that account for the cultural beliefs and behaviors of older persons.”

It’s evident that Sarada, Pillalamarri and Lim are part of a broader pattern among Asian and South Asian seniors. As an index to policies on older immigrant adults, it helps to examine how and why enjoying the food served becomes critical in staving off feelings of alienation and unhappiness.

The Science Behind It

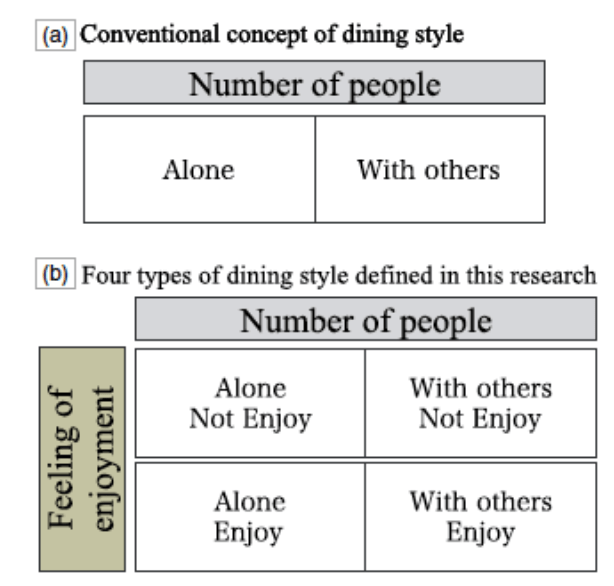

Mai Takase, a Japanese researcher from the University of Tokyo, along with Tomoki Tanaka, Hiroshi Murayama and others conducted a study investigating the connection between food enjoyment and social connections among seniors. Displaying the work on a poster at the GSA conference, Takase explained that they interviewed 190 residents at an assisted living facility in Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan. Questions were asked about meal enjoyment, social engagement: Do you enjoy the meals? How many other facility residents (not a family member) can you talk to about your private life with ease? And the risk of depression was assessed.

The findings indicated that meal enjoyment was critical to emotional health, even if the senior had an extensive social network. “There was a higher likelihood of depression among those who did not enjoy the meal,” summarized Takase.

In a follow-up study at the same assisted living facility, the same group of researchers looked at whether eating with others, as compared to eating alone, in connection with enjoying the meal, had any influence on the respondents’ emotional moods. The subjects were broken into four different groups. Those who enjoyed the meals and ate with others; those who did not enjoy the meals, but ate with others; those who enjoyed their meals but ate alone; and those who ate alone and didn’t enjoy their food.

The figures were extracted from the Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, published on 9/12/19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2019.1662356

Takase explained that while cross-sectional studies found that seniors who eat alone are more likely to be depressed, this particular study concluded that not enjoying the meal was a significant contributor to depression, regardless of whether it was consumed alone or with others. “Our findings indicate that the feeling of enjoyment (a subjective aspect of dining style) is an important factor of eating in assisted living facilities: not enjoying meals may be a major risk factor for depressive mood,” wrote Takase.

Aligned with these conclusions, Sarada, Pillalamarri and Lim’s focus is not necessarily on eating with others, but enjoying their meals. Sarada consents to eating in company only if she is assured that the food being served is what she knows and likes. It’s evident that food desires reinforce cultural identity and drive cultural and emotional stability for these senior immigrants.

In contrast, there are other seniors who show remarkable food, cultural and social adaptability. So, it’s perhaps interesting to understand why that is the case.

“I’m not fussy about food”

Sita A. celebrated her 91st birthday recently. She has been living in New York with her daughter, Ashwini, since the 90s. Sita grew up in Coorg, a hilly town in the south of India. Her mother died eleven days after Sita was born and she was reared by the family nanny, Somaiya, who had three children herself. Somaiya was an excellent cook and Sita remembers breakfasts of akki roti with jams and chutneys and dinners of pork, chicken or mutton curry with rice and steamed accompaniments of jackfruit or bamboo shoots.

Later, when Sita moved to Chennai, a busy urban city, to raise her daughter on her own, necessity drove her to improvise. “It was tough being a single mother initially with no proper income,” she said. But she found her feet, selling her jewelry and finding a job. This gave Sita the training to adjust to new situations she encountered, particularly as she aged.

When I was a college student in Chennai, I used to visit Sita at her studio apartment down the road from my college campus. I recall once sharing her simply prepared dinner of soy nuggets and tomato soup. The taste of that meal has far outlasted the flavors of any meal I’ve had since.

Sita moved in with her daughter and son-in-law in the late ’80s and readily adapted to the places they’ve lived in, including France and Scotland, where she built a strong network of friends.

“I’m not fussy about food,” she told me when I visited her in upstate New York. She went through her daily food regimen with me, mostly stressing the time of day that she has her meals and how important her tea is to her. She enjoys eating with the family and is happy to sample whatever has been cooked, she said. I reminded her about her love for kohlrabi. “Yes, you know me well,” she agreed, “I love noolkol [kohlrabi] with mutton curry, and Ashwini makes it for me,” she said, the familiar tinge of pride infusing her tone when referring to her daughter.

The Priya Living Experiment

In the winter of 2015, my family and Sita’s family took a two-week vacation to the Bahamas. Sita agreed to accompany us on the vacation, but Sarada flatly refused. The idea of leaving an 82-year-old woman alone seemed irresponsible, so I signed up for a one-month stay for Sarada at Priya Living, a retirement community in Santa Clara, California.

I took Sarada to check the place out. “Look, you’ll have your own apartment and you’ll be with others your own age. There’s a full kitchen, and you can make sambar and kootu.” She looked stubbornly unhappy and said she was not going to cook and that I’d need to figure out her meals. There was a little evening get-together that day and I introduced Sarada to many who welcomed her into the community with a warm word and smile. Beyond nodding politely, she sat without saying a word.

Feeling perturbed, yet hopeful, I settled Sarada at her new place a few days before I was to leave and got a commitment from a young woman who lived a few doors down to check in on her at least once a day.

When I called the first time, Sarada complained about how the place was too quiet. When I suggested she attend the daily meet-ups in the lounge, she said she wasn’t interested in meeting anyone.

Before leaving I organized a daily meal program for her, a service that many others at the senior community center recommended. Sarada, however, didn’t care for the Gujarati (west Indian) food that was delivered.

All the while, at the beach resort, while I was worrying about Sarada, I observed Sita taking to the new environment, making casual conversation with strangers, and tucking in to risottos and salads with nary a murmur of discontent. The day I came back home from my vacation, I went to Sarada’s apartment. I found her by the door, packed and ready to leave. She told me she’d started packing four days before I was to arrive.

So what’s different about Sarada and Sita?

Sita and Sarada have different life experiences. Sarada grew up in Moncombu, in the state of Kerala and then migrated to Pandaveshwar in the state of West Bengal after she got married. Moving from the deep south to the north was traumatic for her, a young woman who’d lived a sheltered life, within the confines of her village. She found everything about the north Indian culture alien. Over the years, she began to adapt to her new environs. However, to be clear, she went from a small village in south India to a small village in north-east India. There was little in terms of restaurants serving non-local or global food options in these hard-to-access locales. And for most of her life, she had never been exposed to urban or western culture. These conditions inevitably shaped her response and reaction to brand new gastronomic offerings.

According to Ghatak, easing into a new food culture “depends on whether they tried different foods when they were in India.” Most often, in Ghatak’s analysis, it is those who’ve lived their lives in a particular way without traveling much or eating out who end up dependent on their palate for emotional stability in their new circumstances. In Sita’s case, her spirit of resilience was further enhanced when she had to negotiate a new city and circumstance on her own.

One Solution? Food delivery service that’s culturally relevant

Take the Meals on Wheels program. The program is a federal initiative to help meet older adults’ basic food needs and to help them age in place in their own homes. Research by Thomas and Mor in 2002 has shown how the Meals on Wheels program has kept older adults with low care needs out of institutions such as nursing homes.

Phil Ishida getting things ready for the day’s meal deliveries. Meals on Wheels SF (MOWSF) kitchen staff cook and package between 3,000 and 8,000 meals regularly. (Photo credit: MOWSF)

In a randomized control trial on home delivered meals programs on participants’ feelings of loneliness published in the Journals of Gerontology, the authors, Kali S. Thomas, Ucheoma Akobundu and David Dosa concluded that home delivered meals reduce feelings of loneliness. The reasons for this reduction, the authors surmised, include the daily or weekly social contact as well as the food that’s delivered.

However, what the research failed to point out was what happens when seniors find the delivered meals dissatisfying. Essentially, what works for the native-born population will not necessarily work for the first-generation immigrant cohort.

“It’s pretty unreasonable,” remarked Myong Sool Chang, editor of the Boston Korea. “Lim’s is not the story of one old man.” Korean American seniors are not accustomed to speaking English, and so it’s a three-fold problem. “There’s a language barrier, there’s a cultural barrier, and there’s no contact point to ask for help.”

Food is a pipeline to mental and physical health and the lack of institutionalized culturally relevant options makes immigrant seniors very unhappy.

Lim craves Kimchi and Korean food and it distresses him immensely that he’s unable to get it.

Ghatak and Shyam luckily located an older immigrant lady from Andhra Pradesh in Milpitas, about 25 miles away, who prepares weekly Andhra meals for several senior clients. This catering service has plugged the food gap for Pillalamarri, much to Ghatak and her husband’s relief.

These days, Sarada is unable to cook full meals for herself and finds my experimental and less traditional cooking habits intolerable. So, a few months ago, when a friend told me about a south Indian food delivery service in the Bay Area called Mylapore Express, I decided to try it out.

As I unpacked the containers that were delivered one Wednesday morning, Sarada eagerly read the labels aloud, “vadai more kuzambu,” “murungakkai sambar,” “lemon rasam,” “beans paruppusili,” “kathirikkai karamadhu,” “pavakkai pitla.” Her face flushed as she saw the bounty displayed before her and she told me how much she loves kathirikkai (eggplant) and pavakkai (bitter gourd). There was no mistaking the thrum of excitement and animation.

Jay Jayaraman, the founder of Mylapore Express, remarked about the number of people who mention their parents when ordering food from his business. He related the story of a customer’s parent who’d gone out of town and on the day that was scheduled to return, upon finding out the Mylapore Express menu, asked his daughter to save the kathirikai for him. Another texted Jayaraman: “We mainly order for my father-in-law. He is happy with such freshness and taste of the food. The keerai masiyal, mixed veg, kootu, aviyal (just to name a few) are the toppers.” As we finished our conversation, I told Jayaraman that his food delivery service maintains the emotional balance in our house, and he chuckled, assuring me that I’m not the only one.

Typically, older immigrants have limited English proficiency, have weak ties to social institutions and little U.S. work experience, according to Judith Wilmoth of Syracuse University. Sarada fits the broad patterns of Wilmoth’s analysis. She arrived in the United States in 2006, became a citizen in 2013, has limited English proficiency, no U.S. work experience and is unworldly in most respects. But there’s little to nothing wrapped up in that description.

Sarada is a nurturer who smuggles fruits into my backpack on the mornings she sees me rushing to make my morning train. She does the dishes when I’m too tired to do it. She feeds the family dog, and worries about my adult children’s eating habits. In small and large ways, she is an essential link in the chain of my life and her happiness strengthens me.

It’s Wednesday and Mylapore Express has just delivered Sarada’s meals. I open the carton and begin taking out the containers. She comes rushing out of her room and asks excitedly, “What’s on the menu this week?”

Jaya Padmanabhan is a journalist and author. She was previously the editor of India Currents.

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, Journalists Network on Generations and the Silver Century Foundation.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.