by Gina Le. This article originally appeared on the SEARAC blog.

I am privileged to have been born and raised in Little Sài Gòn, the ethnic enclave that Vietnamese refugees carved out of the heart of Orange County, California, and transformed into one of the largest Vietnamese diasporic communities in the world. Here, in the sunny suburbs of California, I was privileged to have never been an anomaly; I grew up surrounded by kids who looked and talked like me. Just the “Nguyễn” section in my high school’s yearbooks consistently spanned hundreds of names. I even wrote about Little Sài Gòn in my college admissions essay, opining at length about entire blocks of small businesses without a single sign in English, and about the practice of Vietnamese American code-switching that came to me as easily as breathing.

(Clearly, someone found my love letter of an admissions essay promising, since I’m now in the last stretch of my undergraduate career at the George Washington University.)

Coming up on almost four years of that trial by fire (because, yes, attending a predominantly white institution as a first-generation person of color is just as great of an ordeal) has given me a wealth of time and space to reflect on my community. There are times–more frequent than I’d like to admit–that I’m homesick for a steaming bowl of truly good phở that doesn’t cost an arm and a leg, or for the sound of aunties gossiping in rapidfire Vietnamese.

Coming up on almost four years of that trial by fire (because, yes, attending a predominantly white institution as a first-generation person of color is just as great of an ordeal) has given me a wealth of time and space to reflect on my community. There are times–more frequent than I’d like to admit–that I’m homesick for a steaming bowl of truly good phở that doesn’t cost an arm and a leg, or for the sound of aunties gossiping in rapidfire Vietnamese.

But the benefit of time and distance is that you can gain some semblance of objectivity–or at least, a perspective that’s less myopic than it once was. I like to think that I’ve struck a solid balance between being grateful for everything that growing up in Little Sài Gòn taught me, while also recognizing the serious issues that existed when I was too young to name them, and continue to exist today.

Politics is a tricky topic for probably every family in the United States, but it’s particularly fractious for Vietnamese Americans, whose every political maneuver exists in the long shadow of our arduous and traumatic journey to the United States. I am, of course, talking about the War (whose very name is a source of controversy, and with good reason).

What often only takes up a few pages of your average American history textbook under a subheading titled “The Vietnam War” is the story of displacement for hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese refugees and, for their children, inherited trauma. Though decades have passed since the War and now, it’s difficult to minimize the enormous impact of the War on Vietnamese Americans of all ages.

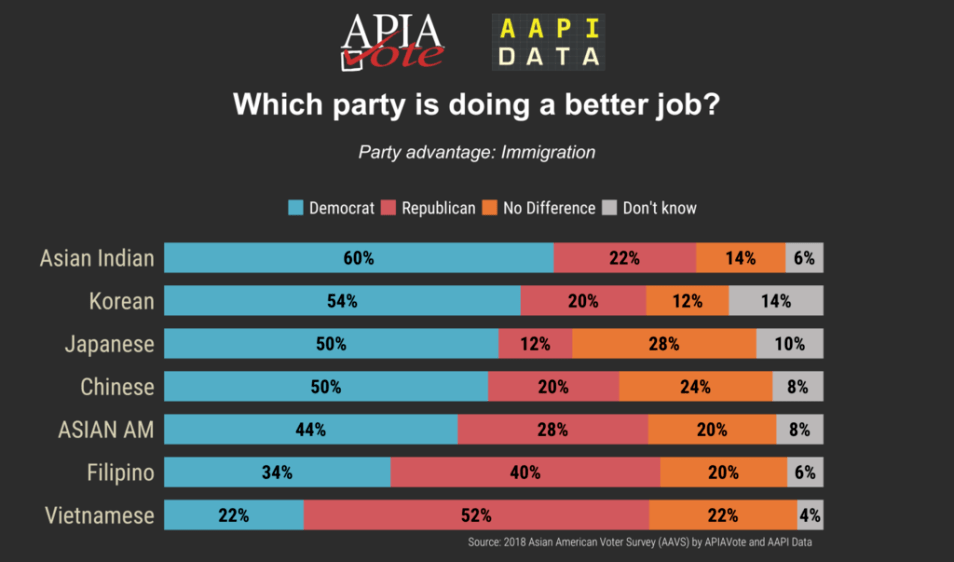

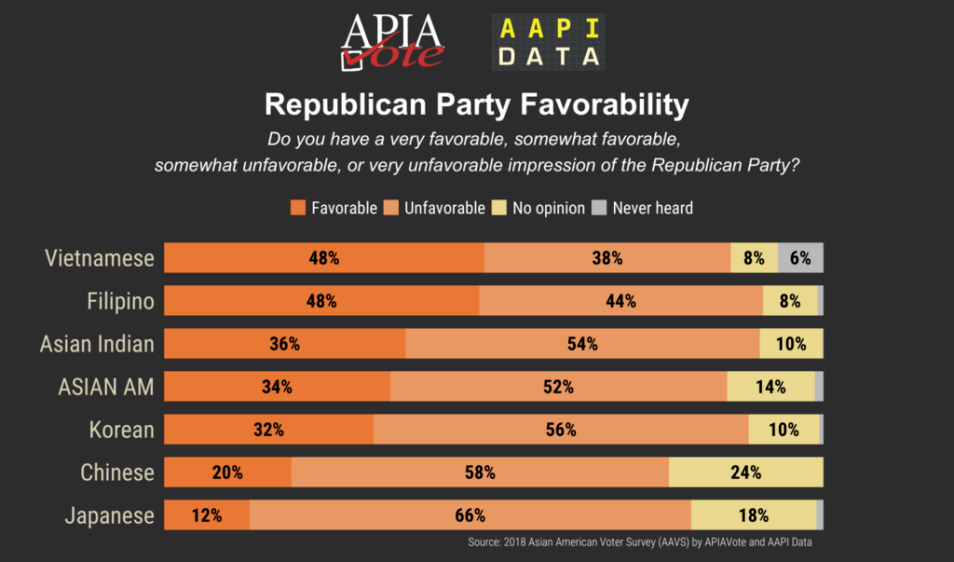

It’s especially important to consider this context when current data indicates that Vietnamese Americans are still, by and large, supporters of the Republican Party—the party historically credited with “supporting us during the war,” “bringing us to the United States,” or some variant of the two. This staunch conservatism in the Vietnamese American communit—particularly in a historically red county like Orange County—extends beyond simply historic party loyalty. It extends to active support of Republican policies that aim to limit migration and impose restrictions on immigration. In short, the Vietnamese wartime refugees and their descendants continue to support policies that would have barred our own entry into this country.

I love my community, and I love the people that make it up. But I firmly believe that to truly love something, you have to know it even for all its flaws and pitfalls. And I believe that it flies in the face of everything it means to be Vietnamese—to overcome obstacles, to care for your family, to show generosity to others even when you yourself have little—to turn our backs on refugees and immigrants of today.

***

I haven’t celebrated Tết in years, since I’ve been away from home. Being away from my family during Tết means that I don’t get to participate in some of the hallmark traditions, like playing bầu cua cá cọp, lighting firecrackers, or buying pots of hoa mai.

But my mom always finds a way to send me lì xì every year—as she did this year. I called her to chúc Tết, or to wish her blessings for the new year: for money to flow into her pocket like water, for good health and fortitude.

If I could chúc Tết for my community, I would wish for them the following:

- For money to flow like water into their coffers, to hire translators in public offices and fund culturally competent health care (and, maybe, if all the community’s work around 2020 Census pays off, this one will come true)

- For the following year, and hopefully all the years to come, to be one not just of surviving, but of thriving.

And, finally—

- For bravery. For the bravery to recognize that we are so much more than just the starving, traumatized boat people so grateful to be brought to safety. That we no longer owe our allegiance to any person or group that does not serve our interests. And for the bravery to put aside archaic fears of the unknown, and reach out with compassion to those that need it most.

As of January 2020, Gina is SEARAC’s new Field Associate. She was previously a Field and Communications Intern through the summer and fall of 2019.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.