By NARGIS HAKIM RAHMAN. This article originally appeared on Tostada Magazine.

Growing up in my Bangladeshi family in Hamtramck, I could literally hear someone turn on the shower next door. In the summer months, I could almost eavesdrop on entire conversations taking place through the windows. When I was younger, I remember having to keep the curtains closed at all times because our neighbors could see everything in our home if we left them open.

With homes less than five feet away from each other, often separated by only a narrow breezeway, people are cramped into one or two-story bungalows and two-flats. In some cases, two or three families live in intergenerational households, consisting of aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents. In addition to focusing on getting good grades, doing chores, and watching over siblings, many younger family members serve as part-time caretaker for their older relatives. Helping with meal preparation, filling out important forms, translating messages from English to Bangla are all common tasks. According to Bangladeshi tradition, it’s the responsibility of the younger family members to ensure that the older generation was unencumbered by undue burdens. In my first few years of marriage, I found myself beginning to take on this role as well.

It wasn’t until I moved to Warren to raise my own family that I could finally draw the curtains and let some light and air inside without worrying about the neighbors being able to peek inside. Our neighbors here are more than an arm’s length away. They tend to keep to themselves. The most we see each other is on the driveway where we exchange pleasantries.

In COVID times, I can’t help but think about this contrast when I look at the alarming number of people in my adopted hometown of Hamtramck who’ve been impacted by the pandemic. In cities across America, Black and Brown residents have been sickened or died at much more alarming rates and under much more dire circumstances by the spread of COVID-19. An inability to social distance — either because of economic hardship or because of cultural norms — a lack of access to reliable information in languages other than English, and a dearth of data available about how specific ethnic populations are hurt by the virus all illustrate the many vulnerabilities that immigrant communities face during this crisis.

Older Bangladeshi women, in particular, are among the most vulnerable to being infected and are also far more likely to be exposed to misinformation because of this reliance on younger generations conveying information, often unverified, to assist with daily life.

With a population of about 22,000, Hamtramck has the largest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases — 1,815 — of any small city in Wayne County, according to county data. The city ranks at 10 in Wayne County, trailing cities that are as much as three times its size. While cities like Dearborn and Dearborn Heights — other largely immigrant communities — have higher rates than Hamtramck, the sheer density of the city is especially troublesome to public health experts. Hamtramck is one of the densest cities in Michigan, making social distancing measures like quarantining alone untenable.

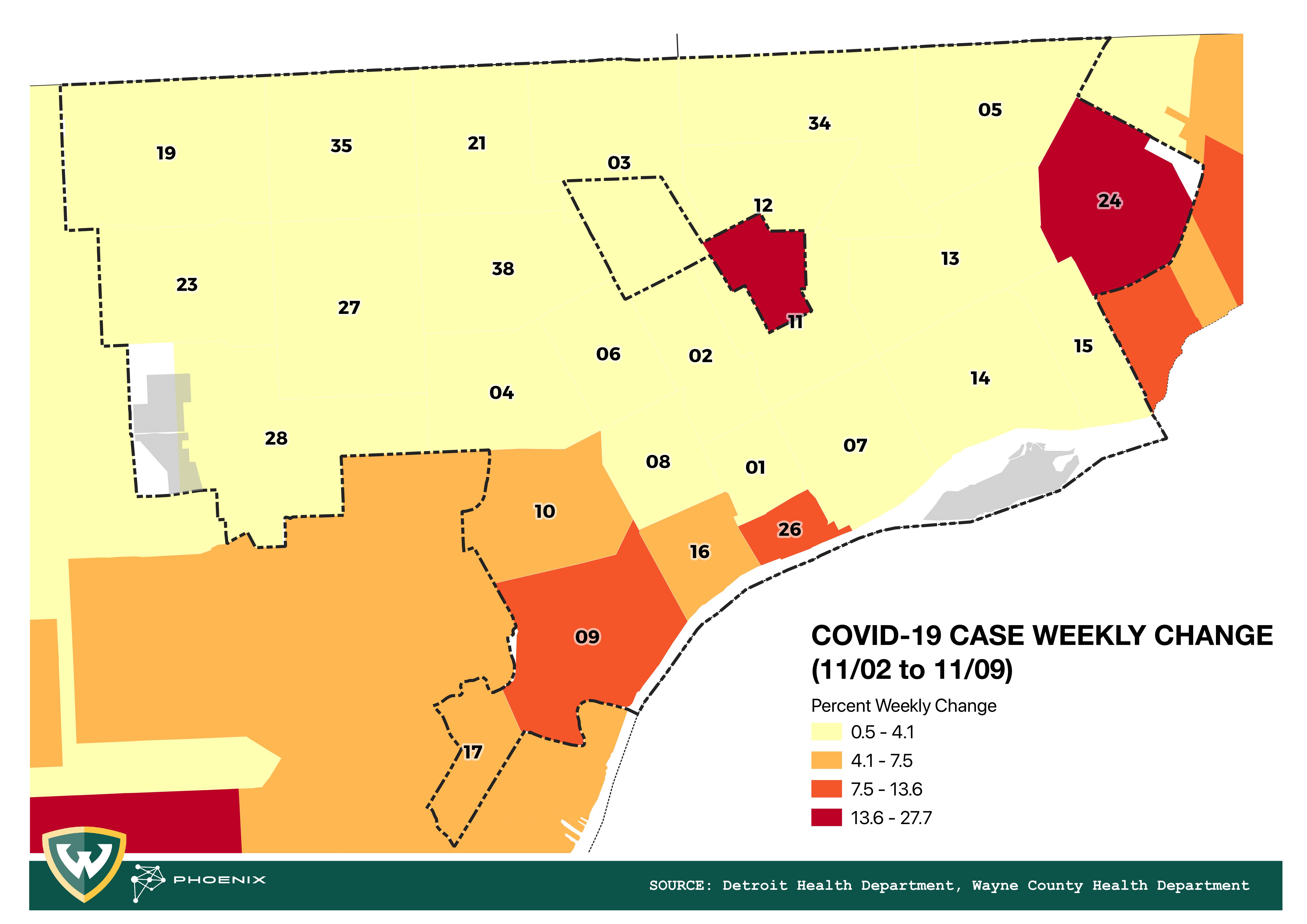

Alex B. Hill, Geographic Information Systems director with Wayne State University’s Center for Translational Science and Clinical Research Innovation’s PHOENIX Project, says Hamtramck has repeatedly shown up as a major hotspot for the spread of COVID-19 in Metro Detroit in 2020, including a sharp spike in early November when cases jumped 13 to 27 percent in just a single week.

“There were weeks where we were like, ‘holy crap, we need to get to Hamtramck,’” says Hill, whose work with the PHOENIX Project involves tracking reported cases of COVID-19 each week throughout the region and uses that data to inform where to send a fleet of mobile testing sites.

In the days following the Nov. 3 election, the Hamtramck City Clerk’s office was closed temporarily after the city clerk and at least two employees tested positive for the virus. In August, Mayor Karen Majewski also tested positive.

According to an interim report published in December by the Michigan Coronavirus Task Force on Racial Disparities, as many as 10,700 Asian American Pacific Islanders had a “cumulative confirmed probable COVID-19 cases and deaths in Michigan per million,” between March 1 and October 31, 2020. The task force was created by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s office to track and report on these disparities while increasing access to health services.

What statistics do not show are the many ethnicities that fall into that racial category, making it difficult to track how specific ethnicities or nationalities are impacted by the virus. Similarly, while a large portion of Hamtramck’s population is of Arab backgrounds, that number is not reflected in Census data. At least 80 percent of Hamtramck’s population comes from Black or Brown backgrounds. Bangladeshis make up nearly 30 percent of the city’s population and are also the third-largest concentration of Bengali immigrants in the United States. About half of Hamtramck is estimated to live below the poverty line and about two-thirds of adults in the city speak a language other than English. The population is constantly fluctuating as many people move out of town as they move up economically and relocate to more affluent suburbs.

As part of the Journalists in Aging Fellows Program, I will be writing a three-part series in partnership with Tostada Magazine on Bangladeshi older adults, especially women, and how local leaders combat misinformation in immigrant communities amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the coming weeks, be on the lookout for the first in our series in which I’ll unpack how the Bangladeshi community is especially vulnerable during the pandemic. I will also look at how language access plays into the crisis, followed by reporting on the solutions that groups are coming up with to address these disparities.

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations and the Silver Century Foundation.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.