All too often, history is written by those in the mainstream, and the stories of marginalized communities – the stories of our elders – are lost. A team in St. Louis is working to recapture and map the history of LGBTQ communities in the region, and last month, they unveiled their interactive online map that documents queer history across the city from 1945 to 1992. Researchers identified 800 locations that were important to the LGBTQ communities in St. Louis during that time, including bars, bookstores, HIV clinics, cruising spots, protest sites, and locations of police raids and arrests.

Sherrill Wayland of the National Resource Center on LGBT Aging, who lives in St. Louis, attended the launch event for the Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis project back in October. “As I sat in the audience listening to LGBT older adults share their stories,” Sherrill says, “it struck me – I came out in 1992! To hear first-hand of the challenges, struggles, and triumphs of the past reminded me that their history shaped my history and the work I do today. LGBT older adults have paved and continue to pave the way for LGBT equity.”

The Diverse Elders Coalition reached out to two members of the team that put this mapping project together: Dr. Andrea Friedman, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis and Steven Brawley, founder of the St. Louis LGBT History Project. We talked with them about the process of building this map, the stories they uncovered along the way, and what’s next for the collaboration.

Tell me about you and your organization.

Andrea: I am a professor of History and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. My research focuses on the history of gender and sexuality in the 20th century United States, and I am particularly interested in issues related to democracy and its contradictions.

Steven: In 2007, I started a blog about LGBTQ history in St. Louis. I did that because some of my elder friends had started to pass away, and I knew that their stories were getting lost. Through that blog, I came across a number of community leaders and partners who became volunteers for the now fully formed St. Louis LGBT History Project. We have archival partnerships with the State Historical Society of Missouri, Missouri History Museum, and Washington University in St. Louis (our map partner).

Early in the process, project collaborators attend a workshop on the possibilities of digital mapping for queer history.

Tell me about the Mapping LGBT St Louis project.

Andrea: This project actually originated with the library at Washington University. Our former head librarian had been working with the St. Louis LGBT History Project and the Missouri Historical Society to find materials to tell the story of LGBT history in St Louis. The library contacted my department to see if we wanted to participate, and from there, we came up with this idea of a mapping project.

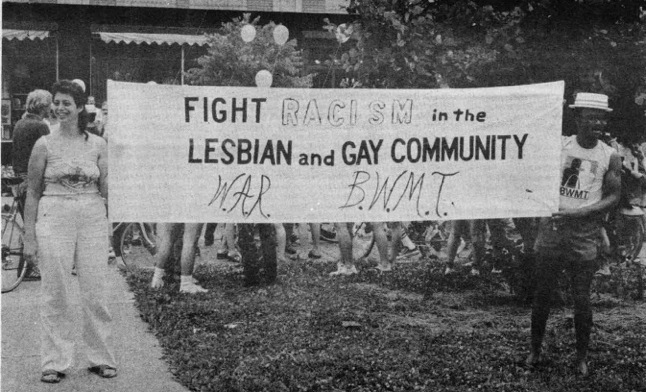

The reason we decided to do this as a map project is because there were some key resources at the university that we could tap into. St. Louis has been a focal point of inequality in recent years, especially as it relates to policing and communities. We came up with the idea of looking at the relationship between sexuality and segregation. Mapping seemed like a great way to visualize how they informed each other.

Steven: We wanted to add LGBTQ history to the work that the university was already doing around the history of racial segregation in St. Louis. We learned from people around the country who had already done projects like this, but we wanted our map to be more than just a series of dots – we wanted to dig deeper and really highlight the history and the meaning of these places.

What were some of the biggest challenges in putting together this project?

Andrea: I had no experience with mapping and GIS [graphic information systems] when we started. Projects like this can be really labor intensive. We were able to hire a team of student researchers and library GIS specialists were available to help us with this project. We were lucky to have the university resources at our disposal.

Another challenge is that St. Louis has a long LGBT history, but it has remained untold. The LGBT History Project had compiled lists of bars, organizations, and events, which was a great help. Still, we were almost starting from scratch. It is a challenge to excavate history that has, for many years, remained on the margins.

Steven: A big challenge was narrowing the scope and defining the years – obviously history didn’t start in 1945 and end in 1992. But we had to make sure the project was actually achievable. We also had to audit the potential sites to make sure we could find them and identify the deeper histories that were associated with each. Thankfully, we had a team of student researchers through Dr. Friedman who helped us comb through newsletters, newspapers and other sources. As a result, the map is really diverse and really interesting. Our history is complicated. The stories of struggle are included right alongside the successes.

The map examines how St. Louis’s long history of racial segregation and inequality in St. Louis shaped the LGBT community.

What was the most rewarding thing about this project?

Andrea: The project kind of took over my life! It has radically changed my own research direction. I have decided to do an oral history project as a way to continue the work, and my students are interviewing LGBTQ elders, particularly those who are often left out of these histories.

We had 190 people at our launch event, which was a great turnout. So many elders from the region have reached out to us to say how much they love the resource and how important this has been to them, and they’ve even been helping us to develop further the stories. I’ve been able to meet a number of people from communities I didn’t even know existed.

Steven: As we were uncovering new places and new histories, every day felt like my birthday. We enjoyed a sense of adventure as we were learning about the newly discovered. LGBTQ legacy sites. We were happy to include LGBTQ elders in our process to ensure their stories were heard. I also loved that there was no sense of competition among the map’s partners. We were all united for one goal.

What would you suggest to other communities who want to do this?

Andrea: Mapping is a great technology for everyone to use, but potential project creators should keep in mind that sometimes simpler is better. Finding locations can take a lot of time; we spent hours and hours poring over city directories and local archives.

It is also useful to be able to consult with people who have a deep memory of their experiences in a particular place. We were lucky to have community activists who have already been doing the work of collecting their history and their communities’ history. Find those people in your community before you start a project like this one.

Steven: Be realistic about that information-gathering phase. It can be time consuming, and we were very lucky to have the university resources at our disposal. A project like this is about networking. What partnerships exist or could be made, especially with community elders, to help expand your knowledge of the community? We had a base of elders to turn to who could help fill in the gaps of, “Who said this?” or “What happened here?” We could start with those memories and build from there. Reaching out to community elders is essential, as is being as intentional as possible about finding diverse voices. The essays that accompany each pin in the Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis project tell a deeper story than just, “This is my favorite bar!”

What’s next?

Andrea: We envision the map as a living, breathing, growing thing, but our funding is gone, so one of our challenges will be securing additional funding or coming up with alternative ways of gathering information. We plan to continue to collaborate with the partner institutions on this project, for example, the history museum wants to do an exhibition on LGBT history. I plan to continue teaching a class that will utilize the materials from this map.

Project researchers Karissa and Ian showing off their research progress.

We built a community feedback loop into the project, so people who identify errors in the map or who are able to fill in some of the gaps in the knowledge can submit their own documents and memories to improve upon what’s there. Ultimately, we want people to be able to interact with the documents on the map; we want users to be able to read them, to download them and use them in their own research.

And we’re trying to be mindful of challenges that people may encounter as they access these maps, for example, people who aren’t comfortable using the internet or people who can’t absorb information visually. We are trying to raise money to make some alternative ways of accessing the maps.

Steven: In the short term, we will gather additional input from those who are using the map. What new information can the community provide? For the longer term, we want the map to continue to help us both better reach and better represent groups who are marginalized even within our marginalized communities.

Anything else?

Andrea: This project has been so completely different for me. In the past, I have focused my research on policy analysis. I’m 61, I’m thinking about retiring, and yet this project has reinvigorated me, made me excited about the work I’m able to do, and that has been great.

Steven: We’d love to increase awareness of our history beyond the map. If the map has gotten you interested in LGBTQ St. Louis, the St. Louis LGBT History Project offers historical walking tours and hope to do more of that. I’m also the author of “Gay and Lesbian St. Louis,” the first book on the history of St. Louis’ LGBTQ communities, published in 2016. The book and the map have really helped to jog peoples’ memories about the histories of our communities. I’m working on additional published works and film productions to enhance our research.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.