By Barbara Peters Smith. This article originally appeared in the Herald Tribune.

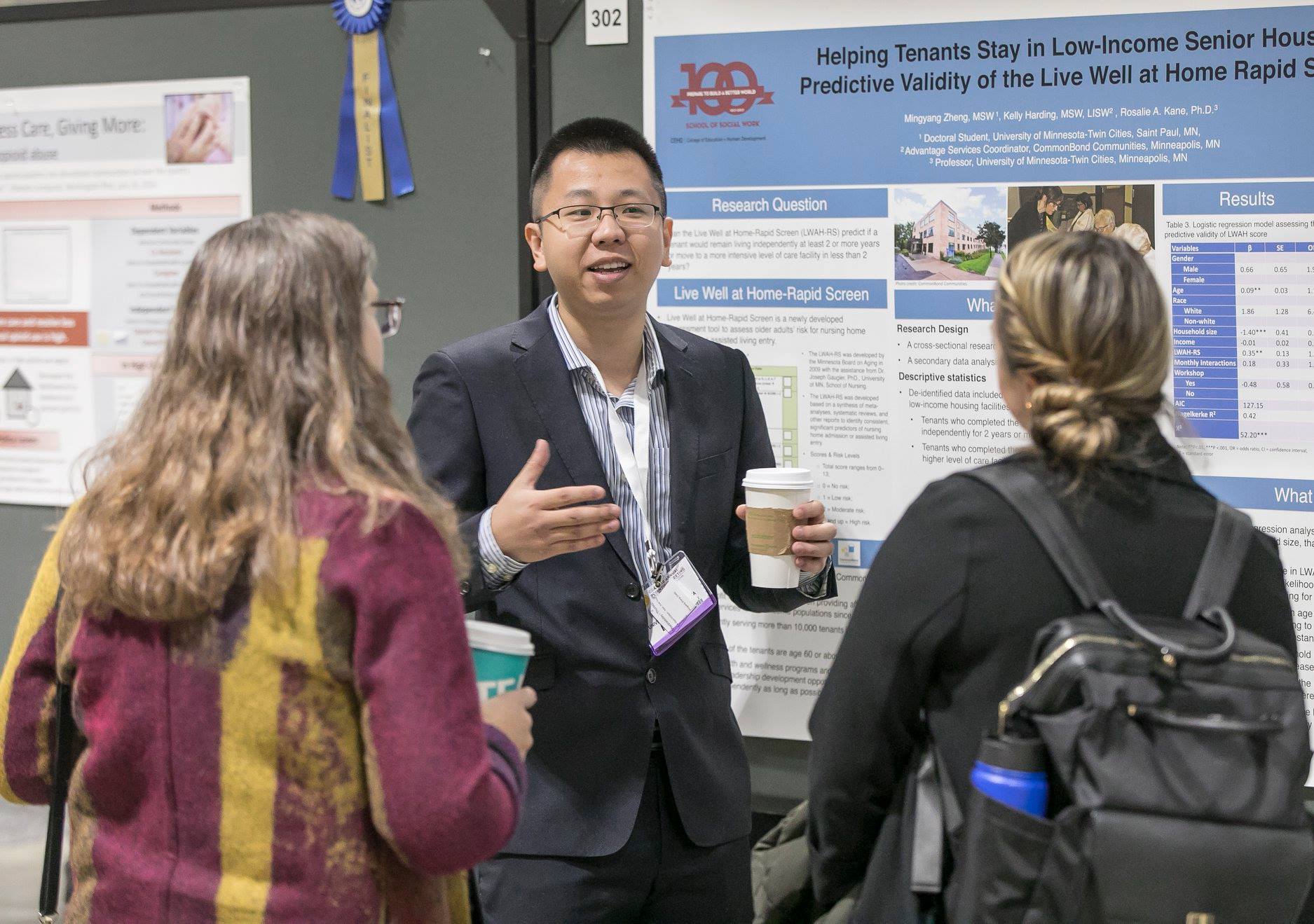

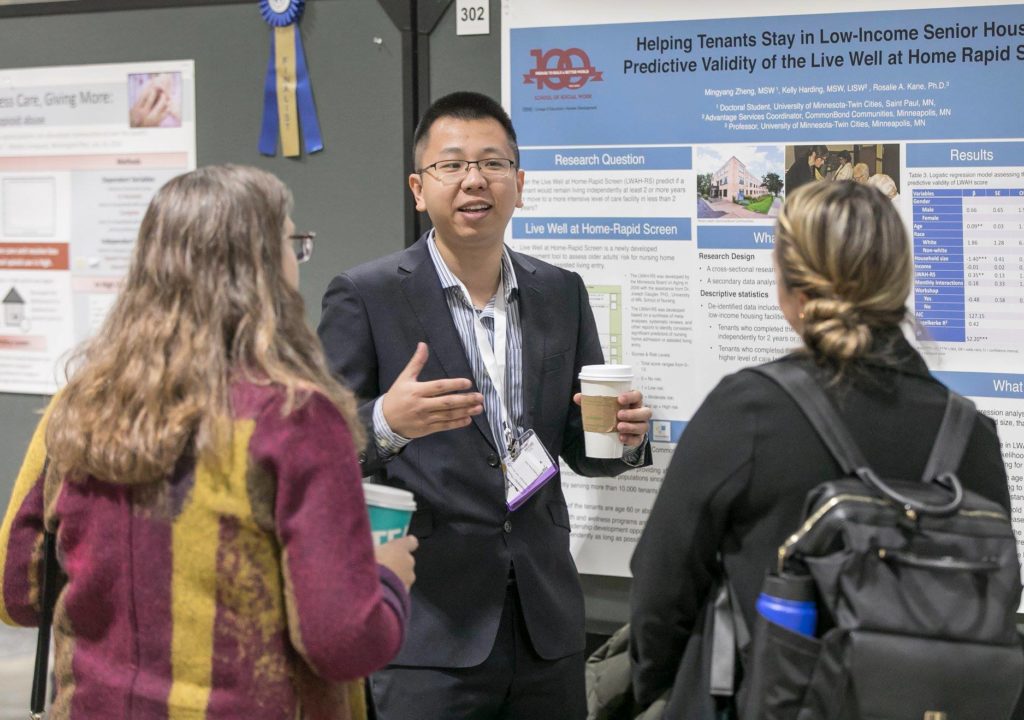

Photo courtesy of the Gerontological Society of America.

The atmosphere at this year’s meeting of the Gerontological Society of America — scientists and social scientists who study the last third of the human lifespan — struck me as less theoretical than ever before. And more, well, feisty.

It could have been the effect of a hotel workers’ strike that made attending conference events a constant moral calculation — with marching and drumming service employees an ever-present reminder of the broadening economic gap between those who get to lie on “heavenly” pillowtop mattresses and those whose task it is to change the sheets.

But it was also clear in the growing body of academic research — as our global population skews older and older — that the aging trajectories of those who stay in hotels and those who work in them are dividing so starkly that little short of radical solutions can restore equitable access to shelter and health care for many of America’s elders. Each year, the numbers become more daunting and the probable outcomes more dire. And so these thoughtful, gentle gerontologists were coming across in their academic seminars as pretty darn radical.

At a symposium moved at the last minute to the beautiful Old South Church so as not to cross a picket line, the notable political economist Carroll Estes recalled the message of the late activist and Gray Panthers founder Maggie Kuhn: “We are elders of the tribe. We can take stands. We can go to jail. We can picket. We can do things in ways that might be unfeasible for younger people.”

Estes and her colleagues made stirring calls for a new kind of “emancipatory politics,” where older Americans lead the charge to broaden opportunities for all Americans.

“We just need to pull together, take this moment,” she said. “Everything is connected; youth and age are one. It’s as if our times have brought us full circle, to where we are seeing the social movements that are burgeoning or budding now.”

Christopher Phillipson, a sociologist at the University of Manchester, spoke of emerging home health care systems that have introduced “a new phase of aging managed in increasingly private spaces.” This allows for “a more unequal old age,” he said, and “greatly increased pressures on older people caring for their partners.”

The longstanding social contract that called for a secure and dignified old age, Phillipson said, has eroded as “the challenges posed by the aftershocks of the recession … pushed gerontologists and others into retreat.”

Steven P. Wallace, a public health professor at the University of California at Los Angeles, spoke out against the current tendency to hold patients responsible for their own health and welfare as a way to trim public spending on medical care and housing.

“The dominant public health approach continues to target individual behavior change,” he said, instead of demanding reform from “the pharmaceutical industry, the junk food industry, real estate corporations and developers. There is a big silence about how those systems came to be and how they are sustained. Why the silence? Who benefits from the policies, and why are they allowed to continue?”

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from the Gerontological Society of America, Journalists Network on Generations and AARP.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.