by Grace Birnstengel. This article originally appeared on Next Avenue.

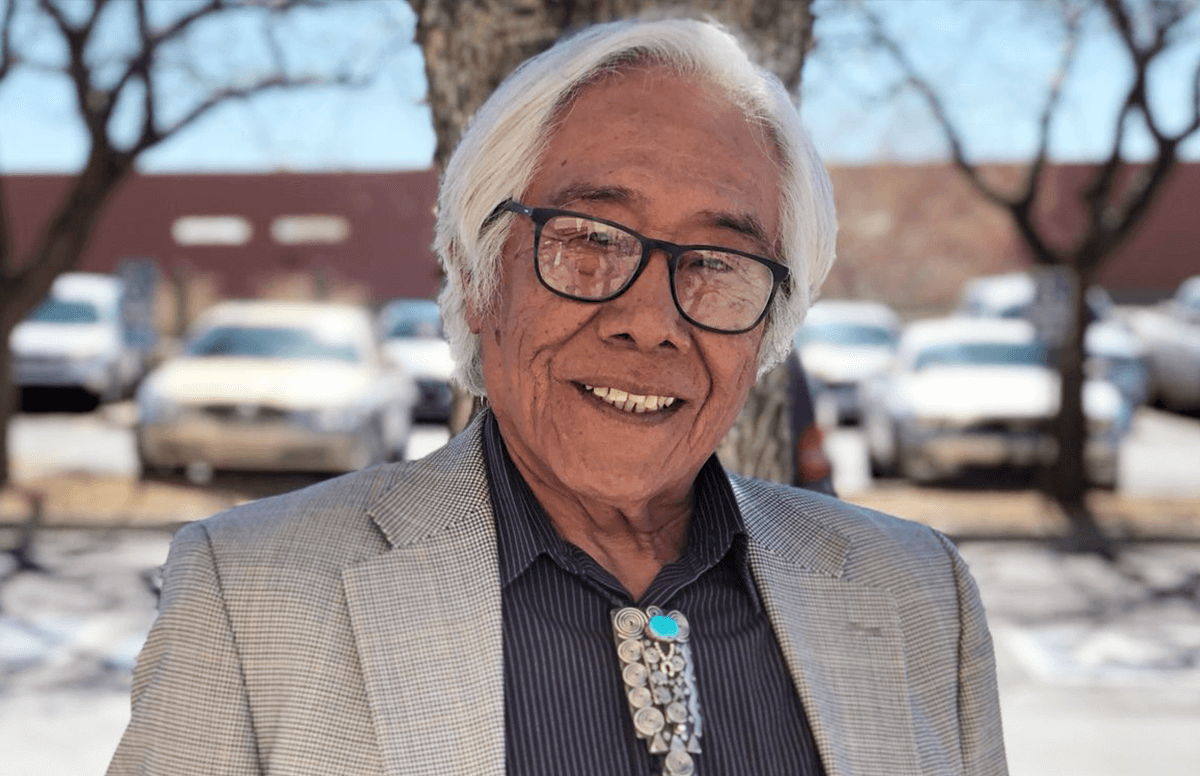

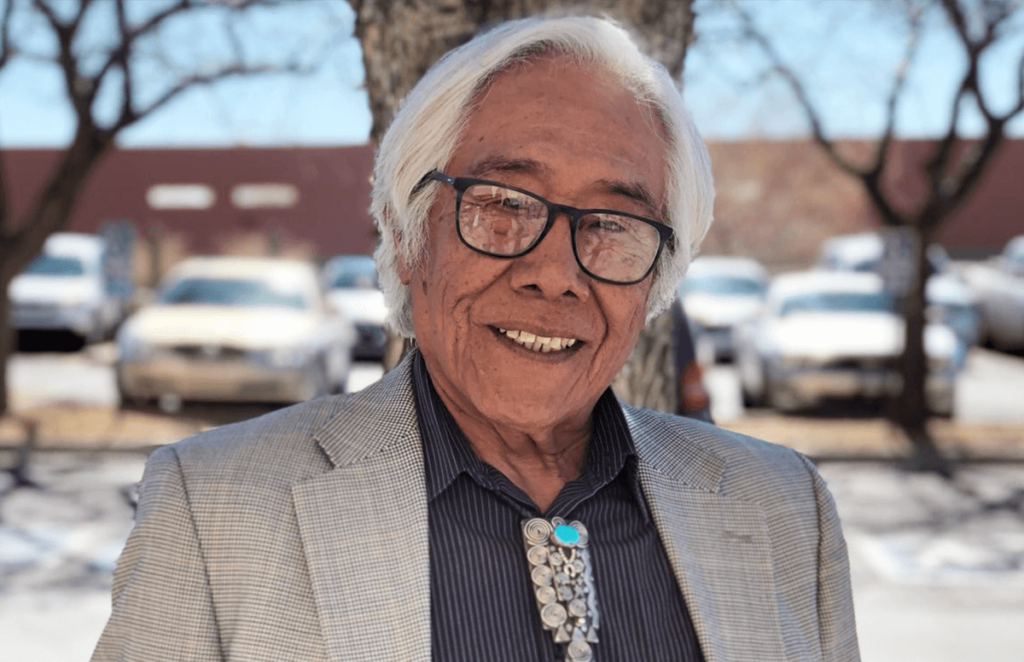

Larry Curley is a member of the Navajo Nation who, with members of the National Tribal Chairmen’s Association, founded the National Indian Council on Aging (NICOA) in 1976. NICOA is a nonprofit that advocates for health, social services and economic well-being for American Indian and Alaska Native Elders.

Curley was instrumental in getting funds directed to Native elders through Title VI of the Older Americans Act in 1978 and spent decades working as a gerontological planner at the Pima Council on Aging in Tucson, Ariz., directing the Navajo Nation’s Head Start program and serving as a nursing home administrator in a tribal, long-term care facility.

Now, Curley’s career has gone full circle, bringing him back to NICOA as its newest executive director.

Next Avenue: You were one of the original founders of NICOA in 1976. What brought you to Native elder advocacy?

Larry Curley: Back when I was at the University of Arizona, I saw a brochure for a program in retirement housing and administration. I thought, every one of us is going to grow old, whether you’re Indian, white, black, whatever. In Indian Country at that time, I knew of only two Indian nursing homes in the country. I thought if I receive my training, I will be more than qualified to run nursing homes in Indian Country.

I [then] did a master’s in public administration and an emphasis in retirement housing and administration. My adviser recommended that I talk to this woman who ran an Area Agency on Aging [AAA] in Tucson. I got into the AAA called Pima Council on Aging. I eventually became the planner for the AAA. When I graduated, I was encouraged to work with the Indian population in the state of Arizona.

I set up an Arizona Indian aging conference in 1975 — the first one. Out of that conference, there were two recommendations: The Older Americans Act was going through reauthorization, and out of that conference I was asked to fight for funds for older Indians. I drafted the original Title X which eventually became Title VI in 1978. The conference also asked for a proposal to have a national conference on aging in 1976. We needed a task force to follow up on the recommendations made. Instead of a task force, we created the National Indian Council on Aging.

I was there at the very beginning, elected to be a member of the board, and from that point on, in 1977, we got funding to create a [Washington] D.C. office, and the board asked me to take that position so I could advocate for the Older Americans Act. In August 1977, I moved to D.C. I eventually took my training to nursing home administration and ran a tribal nursing home.

It’s been a lifelong passion for me. The elderly Indian population are our last link to our language, to our traditions, to the spirituality that’s really important.

I think that we do not preserve those traditions if we aren’t utilizing our elders. I think it’s important that we maintain our identity, especially with some of the things going on in this country right now. Those elders have wisdom and experience.

I am now at the age where I’m eligible for those services I was advocating for when I was in my 20s. I see the changes that have occurred between the elderly population that I advocated for when I was younger to the elderly that we’re advocating for now.

What brought you back to NICOA?

With this organization, I feel like I gave birth to it and it’s my baby, my child. It’s grown into adulthood, but it’s still my child.

When the board chairman asked if I would take the reins, I thought about it and said, ‘Sure.’ I’d be happy to assume the reins of the organization and I want to see how far we’ve progressed.

I’m not satisfied with where we’ve been. We need to continue to look at the future and see where the trends are. That’s the challenge. We need to be ahead of the curve. We can’t just be complacent.

Can you elaborate on your dissatisfaction with where NICOA has been?

When we look at elderly programs — I compare our programs to non-Indian programs — and when you start comparing, there is no comparison. The amount of services available to Indian residents on reservations is severely limited.

There’s practically nothing for Indian country that is comparable to guardianship programs in non-Indian community. We have assisted living programs, and in Indian country, what’s out there is out there is very small. It’s not adequate. To me I see those as challenges.

The other part of it is any decision, any idea we have about improving things, the data is nonexistent. It’s very, very minimal. I worked as tribal administrator working for tribes and one of the big problems is the issue of alcohol and substance abuse, and when you start looking at available programs, how many evidence-based are available in Indian country? Just one. We should be in the field researching.

Why is it that Indian elders are receiving Medicaid benefits as a lesser amount? Fifty percent are below the poverty level; that should be a hundred and fifty thousand eligible for Medicaid benefits. But out of those how many are using the program? They don’t know the answer.

What can we do to make sure that elders are receiving those benefits they’re entitled to? That’s where the dissatisfaction is.

What are the most important issues currently facing aging American Indians and Alaska Native elders?

I served as the director of the Navajo Nation’s Head Start program. Recently, there were studies out that say ninety-two percent of [Navajo] kids don’t speak Navajo at home. That is frightening to me. I am a member of the Navajo Nation. If we are losing young people at that young age, we need to bring the generations together.

Develop more programs. Encourage tribes to develop inter-generational programs for the purpose of reaffirming language and customs.

Back when I was starting out in the field, there was no such thing as Alzheimer’s in Indian people. People said that’s a white disease. And now I’m finding that it’s not true.

One-out-of-five people sixty-five and older will be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or dementia; in Indian Country, it’s one-in-three. Right now, we have a little over three hundred thousand Indians sixty and older in this country. If we are talking about one in three, that’s about a hundred thousand elders who are going to be diagnosed. Each one of those individuals is going to require someone to care for them. We don’t have the number of caretakers out there.

Back when I started, seventy percent of [Native Americans] lived on reservations. Today, sixty percent live off of reservations. Who is left back on the reservations is the older population.

Who will take care of those elders back on the reservation? We think we’ll set up institutional care facilities, then we start looking around and nationwide, of the seventy-two Indian tribes in this country, there are only sixteen nursing homes on Indian reservations in this country.

I know you’re fairly new in the position, but what are you most proud of that NICOA has accomplished since you became executive director?

In November, we raised a flag saying, ‘No, that flag is not white.’ We aren’t surrendering. We are an organization that’s alive, functioning and continuing to advocate for our Indian elders.

We have made our positions known at the national level with our congressional delegation, and we are continuing to advocate. We have come back onto the scene. My staff and my board have been concerned that we are losing our visibility nationally and the effectiveness of our advocacy. We are now looking at the future.

We have answers about where we need to go, how to do it and with what kind of people. I’m proud of the fact that we are reconnecting with the world.

What would you like Americans to know about aging American Indians and Alaska Native elders?

I think what America needs to understand is that those Indian elders are our connection to the past and our connection to the future. This land that we call the United States of America, the ground that they walk on and the dirt they step on, is on the ashes and dust of our ancestors. This land is sacred to us, and they should look at it that way.

Our elders maintain that. We’re still here. We will continue to be here through our advocacy, traditions, language and customs that will continue on to our younger populations. Indian elders are resilient.

Grace Birnstengel is a writer and editor for Next Avenue, currently leading an editorial initiative on age-friendly health care — what it means and how people can identify and access care that meets their unique needs. Her other areas of focus include LGBTQ issues, mental health, the arts and ageism. Grace holds a bachelor of arts in journalism and gender, women and sexuality studies from the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities. You can find her Next Avenue work here.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.