By Richard Eisenberg. This article originally appeared on Next Avenue.

Marny Xiong, Michael Halkias and Yves-Emmanuel Segui

You can learn in The New York Times how many humans have died from the coronavirus from its Tracking the Coronavirus graphic (472,125 as of June 23, 2020). But to understand the humanity, you need to read The Times’ Those We’ve Lost obituary series.

Dan Wakin, who edits Those We’ve Lost, said he wants its readers to get a sense “of the scope of the pandemic; that it spares no one. It doesn’t matter how much money you have, how educated you are, how brilliant a doctor you are. You can die.”

Beyond that, Wakin said, he also hopes readers will “come away with a sense of the slices of our society that are particularly hard hit and a sense of the individual lives.”

Knowing that the COVID-19 death rate for Blacks and Hispanics has been much higher than for whites, Wakin has made a point of running obituaries of people of color.

The Origin of ‘Those We’ve Lost’

Dan Wakin (credit: The New York Times)

Those We’ve Lost began on March 27, 2020 and roughly 50 Times reporters have written more than 200 obituaries of a diverse group of people around the world who’ve died from the coronavirus. More than 300 COVID-19 profile possibilities have been suggested by Times readers. Often, but hardly always, Those We’ve Lost coronavirus victims died in their 70s, 80s and 90s.

The 500-word (ish) stories are poignant, wrenching, sometimes funny, often filled with revealing anecdotes and always remarkable reads. I don’t recall seeing someone described as a “badass” in a New York Times obituary before reading John Leland’s story about Marny Xiong, a child of Hmong refugees who was chair of the St. Paul, Minn. school board and died at 31.

“The stories have really touched a chord with readers,” said Wakin.

The New York Times typically reserves obituaries for the prominent — such as politicians, renowned artists, Nobel winners. Noble people are who you’ll find in Those We’ve Lost. In some cases, the person’s spouse or parent died from the coronavirus, too.

“It’s an opportunity to portray the lives that normally would not be in The New York Times, with a broader range of race and gender and just a much bigger flow of humanity,” said John Schwartz, normally a climate change writer, who has written seven COVID-19 obituaries for the series. They’ve ranged from disability rights advocate April Dunn (who died at 33) to aeronautical engineer Richard Passman (94).

Why the New York Times Journalists Stepped Up

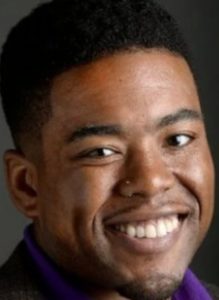

Aaron Randle (credit: The New York Times)

Like many of the reporters asked to write Those We’ve Lost obituaries, Schwartz grabbed the opportunity. “When The Times does something big, you want to be part of it,” he said.

Metro reporter Aaron Randle, who wrote four of the obituaries before his one-year Times fellowship ended, said: “I saw writing the COVID obits as a mix of duty and honor as a journalist.”

He described the experience as engendering “a kind of reverence.” While Randle noted that he “wasn’t trying to lionize anyone,” he did want to “bring a sense of honor to their lives.”

Those We’ve Lost is the third massive obituaries project for The New York Times since 2001.

The first, Portraits of Grief, presented more than 1,800 vignettes of those who died in the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks. The second, Overlooked, began in 2018 and features notables whose deaths since 1851 weren’t covered by The New York Times (mostly people who were not white men). They include Jane Eyre novelist Charlotte Bronte (died in 1855) and journalist Ida B. Wells who took on racism and is described in Overlooked as perhaps the most famous Black woman in the United States during her lifetime (died in 1931).

COVID-19 Obits Vs. Standard Obits

The two chief differences between Portraits of Grief and Those We’ve Lost: The coronavirus deaths aren’t limited to a one-day event and they aren’t restricted to New York City. “This is not a single event like the World Trade Center and 9/11. This is an ongoing crisis. You cannot go for completeness,” said Schwartz.

Another difference between writing a COVID-19 obituary and other ones, the reporters I interviewed told me, was that these deaths were often fairly sudden.

“The thing about standard obituaries is that very often, you’re talking to the family of someone who reached a very advanced age and so these are people who were prepared for the loss of their relative,” said Schwartz. But with Those We’ve Lost pieces, Schwartz noted, often “family members were expecting so many more years. Even if a parent was in his seventies, there was a reasonable expectation of getting ten or fifteen more years with this relative.” The loved one’s relatives, said Schwartz, “feel cheated.”

An Emotional Job

John Schwartz (credit: The New York Times)

That rawness has sometimes made the reporting emotional for the writers.

“You cry. You just cry,” said Schwartz. “It happened to me with 9/11 stories, too. During the interview, you both start crying and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

With obituaries of legends, family members and friends might send the obituary reporter the deceased’s Wikipedia entry. Here, typically, memories are transmitted.

“You sort of feel like you’re joining the circle of mourners,” said John Leland, who wrote the book Happiness Is a Choice You Make: Lessons From a Year Among the Oldest Old. “You’re involved in a way we as journalists often are not.”

Randle reflected: “When I spoke with the families of the relatives of the deceased, I didn’t go in thinking I would find amazingly touching narratives. But often, that came out to be the case.” As time went on, Randle noted, “it did become tougher to remain detached. You kind of carry them a bit with you.”

Randle recalled Dr. Barry Webber, who told his wife “I’m probably going to get” the coronavirus and then did. And pharmacist Yves-Emmanuel Segui, who Randle described to me as “respected in his homeland of Ivory Coast coming to America and not only grounding his family in American life, but having dogged determination fighting ten years to be a pharmacist all over again. Such resiliency.”

‘I Would Do It All Over Again’

The combination of writing the COVID-19 obituaries, the protests about police brutality and Black Lives Matter and being quarantined “all kind of rained down on me and caused a moment of extreme anxiety,” Randle confided. “But there’s not a thing I would regret” about the assignment, he added. “I would do it all over again.”

Some say people who die from coronavirus were old and going to die soon anyway. Leland answers: “A human life is a human life.”

Mary J. Wilson, described in Those We’ve Lost as a “barrier-smashing zookeeper” who died at 83, was one of the coronavirus victims Leland most enjoyed writing about.

A snippet from this lovely obituary: “Ms. Wilson was a sports fan, a trash talker, a fearless woman who stood 6 feet tall. But mostly, Ms. Wilson, the first African American senior zookeeper at what is now the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, had a way with animals, especially loose ones.”

Before Wilson died, Leland told me, “she was out of that game, but still seemed to be living a full, rich life.”

In his obituary, Leland wrote that Wilson’s colleagues and her daughter Sharron Wilson Jackson “said she had never talked about breaking a racial barrier — she just loved her work.”

The People Featured in ‘Those We’ve Lost’

John Leland (credit: The New York Times)

Loving the work and loving people come up often in Those We’ve Lost.

Randle wrote that as the Grand Prospect [banquet] Hall owner in Brooklyn, Michael Halkias “really settled in, and shone.”

Schwartz’s obituary of Orlando Moncada, a Manhattan building foreman who died at 56, noted that “when Peru suffered a devastating earthquake in 2007, Moncada raised money for relief efforts by soliciting people who worked in the office building where he worked. He collected so much, he could fly to Peru and charter a bus to distribute the food, water, blankets and other emergency goods.”

When Those We Lost started, Wakin said, The Times published several of the obituaries a day and one print page a week featuring five or six of them. As the pandemic worsened, the project’s output expanded — to two pages a week, then three and about five stories each day. Now, Those We Lost typically posts two or three pieces a day and is back to two pages a week.

The project’s future is as unknown as the future of the pandemic.

“I can see us going at our current pace for at least through June,” said Wakin. “Beyond that, I can see us cutting back or reducing volume, but I imagine the series will go through summer. Really, I don’t know. It’s hard to predict.”

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.