By Mandy Diec. This article originally appeared on the SEARAC blog.

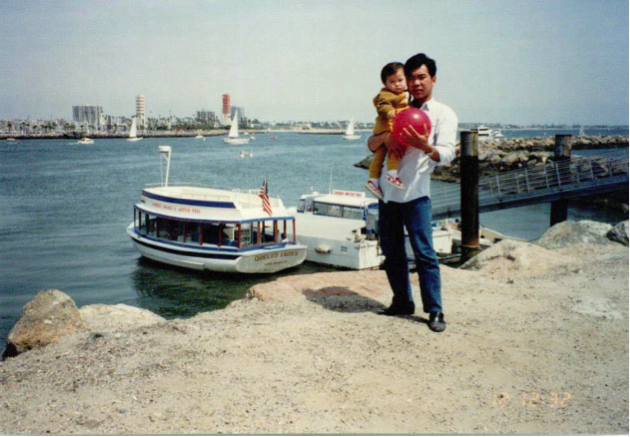

Mandy and Dad, Los Angeles in the early ’90s

In 1991, my family and I arrived in California as part of the final wave of refugees resettling in the United States after the Vietnam War. My dad has retold this story many times. I loved these stories as a child because the focus was always on the lighter, amusing parts of the story, like when my parents tossed away a diaper they were given on the plane because they had no idea what it was, rather than the heavier reality of leaving the traumas of war and persecution* and beginning the fear and anxiety of acculturating and assimilating in this new, adopted country.

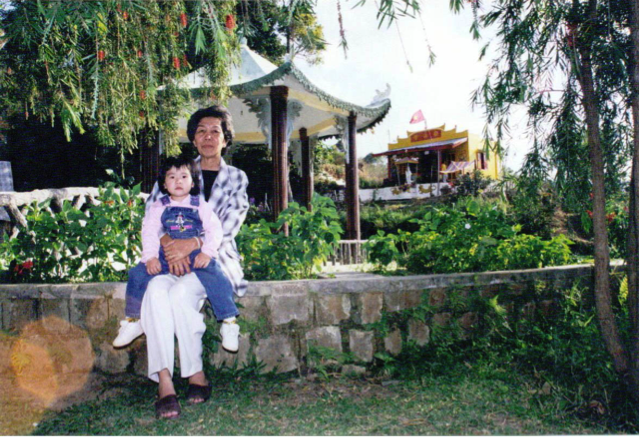

We moved a lot when I was young, from one underserved neighborhood in Los Angeles to another. My childhood memories are dim, but I remember making new friends often and being bullied and treated differently whenever we went. We were poor and part of the Southeast Asian community that had the highest rates of poverty in California in the 90s. I learned to navigate the welfare system early on, from knowing what foods were eligible for food stamps and nutrition vouchers at the grocery store to repeating applications for free-and-reduced-price meals at school. My parents eventually divorced and my paternal grandma helped raise my sisters and me through our childhood and adolescent years, so that my dad could continue to work tirelessly to make ends meet. My dad and grandma worked hard amidst enduring financial, social, and cultural obstacles to give my sisters and me greater opportunity to succeed. I know that I would not be where I am today without their continued sacrifice and perseverance.

Mandy and Grandma, Vietnam 1998

My dad and grandma also made it possible for me to be the first in my family to graduate high school and get a higher education. One day in college, a young Burmese woman from a local refugee resettlement program came to speak in my class and shared her experience living in a Thai refugee camp. Her story would become the catalyst for my early career aspirations in humanitarian aid, relocation to Southeast Asia in search for work, and what eventually became a seven-year career in international development working to reduce poverty and improve health and education outcomes in developing countries.

Last year on the anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, I asked my dad for more detail on what he remembered about being a child amidst a war. He retold stories that I have heard many times before – sitting outside as bombs fell onto the city, dropping out of school early to work and support the family, biking around and caring for his siblings, and having responsibilities of an adult before he was even an adolescent. Then, he told me about the weeks that we spent at a Thai refugee camp, waiting to be processed and resettled into the United States. Almost three decades later, I learned about this important piece of my history. I did not know that back on that fateful day in college, that the Burmese woman and I were connected in a part of our story.

SEARAC was the first organization I came across that helped me better understand, connect with, and make sense of my identity. For the first time, the voices and stories that were uplifted and shared resonated with my own experiences and brought attention to the persistent challenges and inequities experienced by our communities. Almost 30 years ago, my family and I left Vietnam for a new home country that represented the opportunity for equality, growth, and new beginnings. For most of my life however, the difficulties and struggles we endured challenged that notion and the socioeconomic insecurities that our communities faced were often unrecognized and left out of the social justice conversation. As part of the SEARAC team, my story has come full circle. I join the organization with steadfast optimism to build on the incredible progress that has been made to tell our stories, increase engagement and advocacy, create equitable systems, and empower our resilient communities.

*My family is Vietnamese-Chinese, and we belong to an ethnic minority group in Vietnam called the Hoa people. After the end of the Vietnam War, Hoa people faced persecution by the Communist government, where many had their property and businesses taken away and were forced into re-education prison camps for repression and indoctrination. My paternal grandpa served in the South Vietnamese Army, and both of my grandparents underwent the re-education experience.

Mandy Diec is SEARAC’s Director of California. To contact Mandy, email mandy@searac.org.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Diverse Elders Coalition.